Liz Truss’s attempted comeback earlier this week was almost as painful to watch as her premiership. Whoever is advising her obviously forgot to mention “humility” or that it might be an idea to try and acknowledge reality.

But she is right about one thing. In an interview with the Mail on Sunday she said: “I was pushing against a system and against an orthodoxy that was gradually moving to the Left.” She blames her own party for not challenging the New Labour legacy and, somewhat bizarrely, Greta Thunberg. Presumably even Truss has figured out it’s not a good idea to blame the public directly. They must have been brainwashed into socialism by a Swedish teen and George Osborne.

It's certainly true, though, that the public have moved left on a whole range of measures. Today sees the publication of the 40th British Social Attitudes survey which has been running an annual gold standard survey of public opinion since 1983, allowing us to observe trends over time.

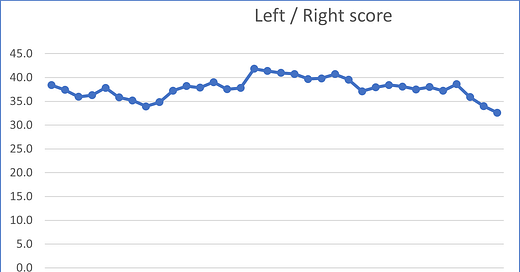

Since 1986 they’ve produced a left-right scaled score based on a composite mix of statements about inequality and the role of government in reducing it (I’ve listed the statements at the end of the post). A score of zero would be maximally left-wing and 100 maximally right. Under New Labour the country drifted rightwards peaking at 42 in 2004, presumably because there was a notable reduction in poverty and an increase in public spending. In recent years it has dropped to 33, the lowest so far.

Left-Right Score 1986-2022

The great thing about BSA is that it gives us a huge amount of detail to help us understand what sits behind this overall trend. And this year’s survey tells us there have been particularly big jumps in the public mood on the role of government in solving social problems and on poverty/welfare. It also raises some intriguing questions about the very substantial age gap in voting behaviour.

The Role of Government

BSA has periodically asked people whether they think government should be responsible for a range of different issues. On things like providing healthcare and help for the elderly support has remained consistently high across the years. There is a strong consensus that hospitals and pensions should be funded. But in the most recent survey there has been a big jump in more disputed areas. For instance, the percentage saying government should “definitely” reduce the income differences between rich and poor has gone from 25% in 2006 to 53% in 2022. Provide a decent standard of living for the unemployed has gone from 10% “definitely” in 2006 to 38% in 2022.

Of particular note is that these shifts have been as strong amongst Conservative voters, albeit from a lower base. The chart below shows the mean score of all the government responsibility questions combined. Labour supporters are roughly back to where they were in the mid-1980s, whereas Tory voters are more in favour of state intervention than at any previous point. This is not a phenomenon that can be explained by lefty woke Thunberg fans. It seems more likely to be a function of important government interventions on covid and energy bills that made a difference to peoples’ ability to weather those storms, as well as the general sense of decay. A small state seems a better idea when times are good.

Mean government responsibility score among Conservative and Labour identifiers – 1985-2022

From the start BSA have asked an annual question on whether people want to reduce the tax burden and spend less on health, education and social benefits; keep it the same; or increase taxes and spending. Over forty years reducing taxes has never got a double digit score. People are profoundly risk averse, and while not unhappy with the idea of paying less tax are not prepared to lose access to current state-funded services or benefits to do so. This is where the Trussites are fighting against the strongest headwind.

Moreover, there has been a notable shift in recent years from “keep it the same” to “increase taxes and spending”. At the peak of the New Labour spending splurge, and the financial crisis, in 2010, “increase” dropped to 31% but by 2017, with the impact of austerity becoming clearer, it reached 60%. It’s still at 55% despite the rising tax burden and cost of living pressures. This is one reason why I think Labour will have space to pivot on tax and spend post-election if they want to – though they will also have to show it is being directed towards genuine priorities. One thing this question doesn’t pick up is the strong public belief, found in other polling, that much government money is wasted.

Welfare

Perhaps the most profound shift over recent years has been around welfare recipients. From 2001 right up to the mid-2010s there was a general belief that benefits were too generous. More respondents than not during this period felt that many people who got benefits didn’t really deserve them. This was the background for the Coalition cuts to welfare. But by 2022 just 19% agreed with that statement.

Agreement that many people who get social security don’t really deserve any help 1987-2022

Again this is not about “woke lefties” but a trend that we can see is even stronger amongst Conservative than Labour supporters. As the authors of the BSA report say:

“This is particularly surprising because the composition of Labour supporters changed with the tumultuous politics of the 2010s; Labour supporters from 2015 were on average less authoritarian than before (with highly-educated, young, socially liberal voters being more likely to support Labour after Brexit and Corbyn), which should, if anything, have made the gap in attitudes between Labour and Conservative Party supporters even larger.”

Agreement that many people who get social security don’t really deserve any help, by political party support, 1987-2019

It’s true that when asked if people would be willing for benefits to be higher even if meant higher taxes the Labour trend line has risen more than the Tory one. But, nevertheless, the change in Conservative voters attitudes is striking and, I suspect, for many readers counter-intuitive.

Nor can it be explained by a fall in readership of those right-wing tabloids that attack benefits claimants most aggressively. Those still reading the Mail, Express, or Sun have become more favourable at more or less the same rate as the rest of the population. One explanation is something I’ve touched on before:

“There has also been a shift away from simplistic media portrayals of poverty. Both ITV and the BBC have, during the current cost of living crisis, done a good job of telling peoples’ stories. Even right wing newspapers who have been happy, in the past, to run endless stories about “scroungers” and benefits fraud, have done so less in recent years. This is partly because some people with experience of scarcity have managed to infiltrate the media world (see this by Catlin Moran in The Times for instance).”

But I agree with the authors that the biggest factor is simply that there has been a real and visible increase in poverty. The percentage who think poverty has risen in the last decade has risen from 32% to 78% since 2006. For the first time over half of respondents reported living in poverty themselves at times during their life.

Changing perceptions of poverty in Britain, 1986-2022

We can also see a change in attitude over what people consider poverty to be – with a sharp increase in the softer definition “if you can’t afford things most take for granted” as opposed to not being able to eat properly or live without debt.

This is what Truss gets most wrong in imagining the leftwards shift is the responsibility of North London champagne socialists or the BBC. The shifts in media/political “orthodoxy” are a consequence of real world changes. Moreover, people are observing what’s happening around them – as they did in the mid-90s – independently of media. And they don’t like what they see. Even if someone is relatively affluent it’s hard to avoid seeing, for instance, that almost 80% of state schools now run some kind of foodbank or food parcel service for parents, and will often be asking better off families to donate.

The Generation Gap

One of the most striking trends of recent years has been the huge age gap that has opened up in voting preference. Older people have always trended more towards the Conservatives but the size of the gap has shot up since 2010.

The age gap in party support, 1983-2022

One might think this is a function of younger people rapidly shifting left or older people right. But, surprisingly, there has historically been little variation between the young and old when it comes to their position on the BSA left-right spectrum. It’s only in the last few years that we’ve seen any divergence (as per the chart below), which is after we saw the shift in voting behaviour, and in any case is fairly minor. One explanation is that older Labour votes have, until very recently, been more left-wing than younger ones on inequality and government intervention.

Mean scores on the left-right scale by age group, 1986-2022

Nor can the large age gap in voting behaviour be explained by changes on the liberal/authoritarian spectrum. Young people have always been more liberal and, while the gap has grown somewhat, it’s nowhere near enough to explain the divergence.

Even more counter-intuitively older people are more likely to support higher taxes and higher spending than younger ones and that gap has gone in the other direction to the voting behaviour one would expect.

Support for increased taxation and spending by age group, 1983-2023

So what’s going on here? The report authors note that Brexit contributed to the age gap growth – though it started before then. But also that the gap hasn’t shrunk despite the EU referendum becoming a less potent issue. It seems more likely that Brexit played into a wider perception that the Tory party has no interest in young people, and it’s this, rather an ideological shift leftwards, that has driven the generation gap.

This would also explain why younger people are less keen on tax rises: they think, probably correctly, it would be them paying, whereas much of the increased spending would benefit older people in need of pensions and healthcare. I’ve written before about changing conceptions of fairness and aspiration, and the growing belief amongst younger people than they can’t succeed just by working hard, a view the government have reinforced.

If all this is correct it has quite profound consequences because it means there is a route for the Conservatives to win back young people by focusing more on their economic interests. It is not a generation lost to them for ever – on either economics or culture. A key question for the next decade of British politics is whether they can signal this without changing position on Brexit – which is such a totemic issue.

The barometer

Commentators often incorrectly assume that because voters typically have minimal interest in Westminster politics – speeches, white papers, parliamentary debates and so – that they are easily misled. Both left and right argue media bias against them leads to misconceptions and false consciousness. This is, essentially, Truss’s argument.

But the BSA data over 40 years shows that voters are well aware of what’s going on around them and respond to real world changes, leading to something of a countercyclical trend in views. As government spending falls, services decline, and poverty increases there is shift leftwards: people want more spending, and more government intervention. As things improve they shift back rightwards.

That doesn’t mean media/institutional behaviour doesn’t matter. For instance, a shift in tone towards benefits claimants may have contributed to public opinion softening amongst Tory voters. But there is only so much media outlets can do to shield their readers or viewers from reality. The Daily Mail cannot hide the growing number of families visibly struggling. Nor would the BBC be able to convince people the NHS was doing well, even if it tried.

As the report authors say:

“The public first began to look to government rather more in the wake of the financial crash of 2008-9, though in the event that mood appears eventually to have dissipated. However, the same cannot be said, so far at least, of the COVID-19 pandemic. Expectations of government in the wake of that public health crisis have never been higher. The public shows no sign so far of wanting to row back on the increased taxation and spending that has been part of the legacy of the pandemic, not least perhaps because of their dissatisfaction with the state of the health service. Meanwhile, there are now also record levels of support for more defence spending. So far as the public are concerned at least, the era of smaller government that Margaret Thatcher aimed to promulgate – and which Liz Truss briefly tried to restore in the autumn of 2022 with her ill-fated ‘dash for growth’ – now seems a world away.”

Ultimately any political party that wants to survive has to respect these trends and work within them. Public opinion may well swing back in the other direction in the future, but for now anyone who thinks the Truss programme is one voters will buy is entirely delusional.

Technical note:

These are the statements BSA use for their left/right composite.

Government should redistribute income from the better off to those who are less well off.

Big business benefits owners at the expense of workers.

Ordinary working people do not get their fair share of the nation's wealth.

There is one law for the rich and one for the poor.

Management will always try to get the better of employees if it gets the chance.

This was political analysis as it should be done. Raising above the soap-opera of day to day political theatre and drawing attention to important long term trends with heaps of reporting of actual facts albeit the facts come from a social survey.

Looking at US and UK politics from afar (Australia) it seems that the conservatives are making the same mistake of paying lots of attention to their loud and passionate extreme members and forgotten that these valued supporters may be a very long way from the swinging voters in the middle who actually decide elections. I know the British Labour made the same mistake with Corbyn and his acolytes but they appear to have learned their lesson from a terrible electoral defeat. Somehow this realization doesn’t seem to be dawning on the culture warriors of the right.

Finally I think there is no question of the Conservatives winning over young voters by ditching Brexit. This will take a generation or to put it crudely the wholesale exiting of large numbers of conservative party members (ie not just the MPs) aged over 60 from the electoral rolls.

Thank you for including your technical note, explaining what the BSA's left-right indicator is made up of. I'll be honest, I don't think these are good questions, they feel like they were drawn up by a left-winger who fails the ideological Turing test (that is, a left-winger who doesn't understand how right-wingers think). The questions seemingly measure up sincere left-wing beliefs against a left-winger's straw-man version of what right-wingers believe - no surprise then that the BSA consistently finds British voters leaning well to the left (as in, less than 50 on a 0-to-100 scale), even as they elect endless Conservative governments.

I would prefer to have seen, as well as the statements listed, some "pro-right" statements. For example:

"Individuals spend their money more wisely than governments"

"Reducing taxes promotes economic growth"

"Big businesses are wealth creators"

Then we might have had a more accurate picture of British voters' economic leaning. As it is, the study asks "is inequality good?", find that Brits don't think it is, and concludes that we're a nation of socialists, even though conservatives don't think that inequality is a good thing either.