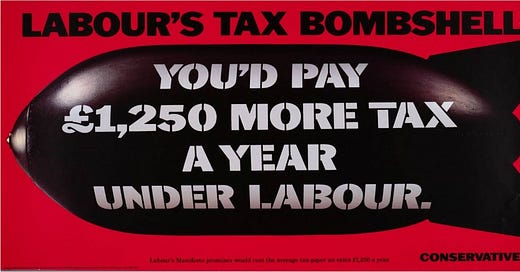

One of the famous adverts that destablised Labour in the run up to the 1992 election

Over the Christmas holidays I read a lot of books about politics in the 90s. Much of the framing around the next election is whether it will resemble 1992, when a deeply unpopular Tory party replaced their leader and managed to successfully scare people about the economic prospects of a Labour government. Or 1997 when a deeply unpopular Tory party got trounced.

But I’m interested in the differences between the broader political environment now and then, and in particular changes in how voters see key concepts like “aspiration” and “fairness”. Back in the 90s it was a new approach to these ideas that underpinned the transformation of the Labour party. Phillip Gould was a key player in that transformation and worked closely with Tony Blair and Peter Mandelson to re-define the party’s image after four election defeats. His “Unfinished Revolution” is one of the core texts of Blairism. The book is infused throughout with an obsessive focus on the aspirational working and lower middle classes, a consequence of Gould’s own early life growing up in Woking.

He was enormously frustrated by the inability of Labour in the 80s and early 90s to speak to these voters and their entirely reasonable desire for a better life, a higher wage, a new car, or a refitted kitchen. The Tories did seem able to offer this, whether by allowing people to own their council flat, offering shares in newly privatised companies that could be sold on for profit, or through tax cuts. All of this came at the price of higher inequality, which was why Labour fought it all so hard. But they discovered that seeking to defend the most vulnerable groups wasn’t enough, by itself, to win an election.

The left-wing conception of fairness as equality, Gould argued, simply didn’t fit with the electorate’s model:

“The view was growing that those who worked hard and behaved responsibly were not being fairly rewarded, while others made gains they did not deserve, had not worked for, were not entitled to….When people are asked what fairness means they invariably answer by one form or another of the same formulation: stop people abusing the system, give people who work hard a fair deal. This problem, at least for the left, is not that the contributory concept of fairness is right wing but that many voters see it in those terms, a powerful idea intertwined with a series of political issues that are more naturally associated with the right: excessive immigration, welfare abuse, wasteful government spending, softness on crime.”

If this seems familiar it’s because it has become doctrinal for the main political parties. How many times have you heard politicians warble on about “families up and down the country who work hard and play by the rules”? As contributory models of fairness or “just deserts” are more naturally conservative this language was already inherent in Tory messaging. After Gould and Blair’s revolution it became embedded in Labour and Lib Dem thinking too. Even Jeremy Corbyn, who despised the Blairite takeover, ended up using the language in his election campaigns, even if he never looked like he believed it.

With Starmer now in charge the desire to connect with voters who think like this is evident. His Director of Strategy is Deborah Mattinson, who worked with Gould in the 90s, and he has other former Blair advisers in his team like Peter Hyman. You can see the determination to stay on message with this part of the electorate in every statement about immigration, crime, welfare and public spending. But unlike Blair it’s not a philosophy that Starmer personally embodies. Blair was the son of an aspirational Tory, for him it wasn’t just strategy or triangulation, it was an essential part of his political identity. For Starmer and most of the current shadow cabinet it feels a bit more strained because they were brought up believing more in the traditional Labour model of fairness (Wes Streeting, raised by a Tory grandad, is a notable exception). This leads to columns like this one from Danny Finkelstein which, not unreasonably, ask if Starmer is more left-wing than he’s letting on. And insofar as he has a policy agenda it is to the left of Blair’s.

How much does this matter? In 1992 Gould, Blair and Brown tried to imbue Labour with a more aspirational message but Kinnock and Smith couldn’t make it stick, and never really got it, at least not in such a visceral way. Some commentators think the same could still happen to Starmer. Writing in the Times before Christmas Rachel Sylvester talked about the risk the fairness dilemma poses to Labour:

“The tension between ‘aspiration’ and ‘equality’ is a fault line that runs through the Labour Party. Around the shadow cabinet table there are proponents of both points of view. Wes Streeting, Pat McFadden and Peter Kyle are passionate about aspiration; Ed Miliband, Angela Rayner and Lisa Nandy lean towards equality. A similar debate rages among the Labour leader’s advisers. As for Starmer himself, one senior figure says: ‘His heart is on the side of equality but his head is with aspiration because he knows that’s what he needs to do to win.’”

I don’t think this is the last time we’ll see a version of this analysis before the election. But it misses some critical differences between now and the mid-90s. And these are worth considering if we want to answer the question as to whether we’re heading for 1992, 1997, or possibly something even worse for the Tories, and what it means for Labour as it starts to think about how it intends to govern.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Comment is Freed to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.