The Real Realignment

Understanding the key voter groups that will decide the next election

The “red wall” has taken on a whole set of mythic properties in British political discourse. This group of seats, largely in the North and Midlands and held by Labour for many years, mostly fell to the Tories in 2019. There is a widespread belief that this was a fundamental realignment in British politics with working class Brexit voters flocking to a socially conservative Tory party. Various Tory MPs and right-wing columnists fondly imagine an army of salt-of-the-earth workers backing their agenda against the out-of-touch liberal elites.

A new report by Professor Jane Green and Roosmarijn de Geus sets out what’s really been going on. Essentially, since Brexit the Tories are doing even better than before amongst older homeowners. Many of these voters do consider themselves working-class, and often have relatively low incomes, but critically they are economically secure because they own property and have few outgoings.

This shouldn’t be surprising. When analyst James Kanagasooriam identified the “red wall” seats before the 2019 election he was looking for constituencies where the demographics were inherently Tory but the seat had stayed Labour out of habit. The point was not that a totally different type of person was deciding to vote for the Conservatives. Instead Brexit had broken historical links to the Labour party that had held people back from voting Tory. As he put it at the time “the history of an area matters – the leave voting 55yr old plumber living in a detached house is more likely to vote Tory in Bournemouth than Wigan, even on the same salary.”

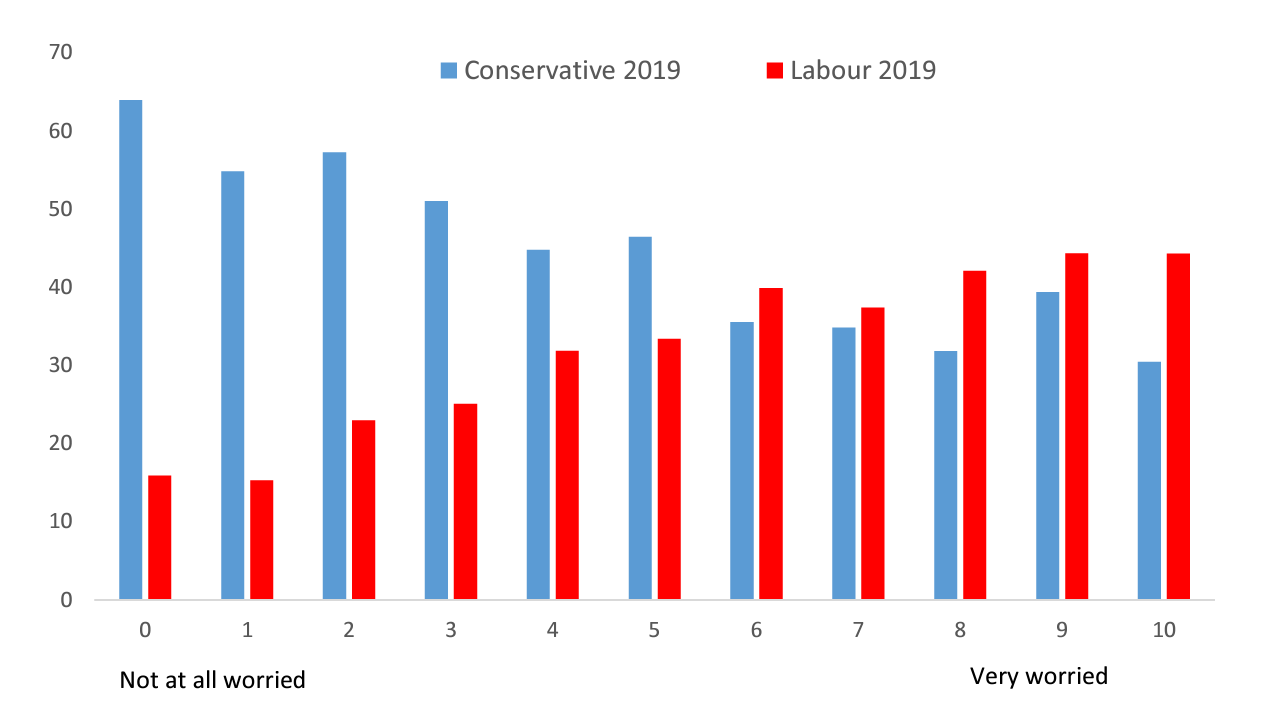

Green and de Geus’s key point is that the economy still matters more than anything else; it is that feeling of security that is most strongly correlated to voting Tory (see graph below). It’s not the only thing that matters: graduates are still less likely to vote Tory, and more likely to be socially liberal, even taking economic security and age into account. It is, though, a critical factor, which is why the cost of living crisis is so risky for the Tories and why Rishi Sunak plumped for a substantial package of financial support this week, even though it dismayed the fiscal hawks amongst his colleagues.

Fig1: Reported Conservative and Labour vote (2019) by economic insecurity (2018), BES internet panel, waves 14-19 (data are weighted). From Green/De Geus report p.50.

This question of economic security goes well beyond immediate support to cover energy bills. As the category “young and economically insecure” encompasses ever more voters, due to the increasing amount of time it takes to get onto the property ladder, they will become increasingly important in elections. In political, if not physical, terms “young” now covers a lot of people in their 40s. Green and de Geus’s analysis should focus our attention on two particularly interesting groups:

1. Younger, economically insecure, non-graduates who are more socially conservative but increasingly poor.

2. Professional graduates who are approaching security much later in life than previous generations.

It’s these groups that will drive the next stage of the realignment.

The real “left behinds”

Younger non-graduates have increasingly bleak prospects. As higher education has expanded, the number of well-paid and high-status jobs available to this group has shrunk considerably, while house prices have gone up. The Tory “red wall” success was largely driven by older, economically secure, non-graduates – but in the long term this is an endangered species.

These younger non-graduates are typically not Tory voters; indeed they are far less likely to vote at all than any other group, though they did turn out in greater numbers for Brexit, which got Leave over the line. They are spread quite widely across the country and are critical to the next election because they are more torn between parties than most voter groups, being generally more pro-Leave, and socially conservative, but also concerned about their financial position. There are high numbers of this group in multiple key marginals like Peterborough and Crawley.

Thurrock is a classic example of a constituency where this group is electorally critical. Over half of residents are aged between 16-49 and are non-graduates. Between 2010-2017 it was a super-marginal but with an increasing amount of support for UKIP. In 2019 this UKIP vote mostly transferred to the Tories and they won by 11.5k votes. For Labour to win it, and places like it, back they need to convince this group that their lack of economic prospects should outweigh their suspicion of social liberalism. They should be able to make a strong case – there has been minimal economic growth over the past 15 years; real wages have been stagnant for that entire period; and the core components of family life, a mortgage and childcare, are now out of financial reach for many.

At the same time there is an opportunity for the Conservatives to build their support further with this group, many of whom are so disillusioned that they don’t vote at all. An agenda that combined social conservativism with a big economic offer would be very powerful. We saw this in France where Marine Le Pen won a majority amongst this demographic by mixing authoritarian language about Islam, immigration and elites with offers such as taking under-30s out of income tax altogether and ramping up public spending. This is an increasingly common model for populist right parties in Europe.

The Tories problem is that their core membership base, and indeed most of their MPs, are fiscal conservatives who want to cut taxes for business and wealthier voters and constrain public spending. Moreover this base, and most of their current voters, do very well out of exceptionally high house prices and benefit from a large pool of non-graduates forced into zero-hours, gig-economy jobs. Probably the best argument for the Tories to keep Boris Johnson as leader is he is the only politician so spectacularly disingenuous that he can promote both these worldviews at once. Under anyone else this tension would appear even more obvious than it already is. But trying to ride two horses is ultimately impossible.

The graduate question

Meanwhile economically insecure graduates are the most solidly progressive voting group there is. Cities are full of them, which is why the Tories barely hold any urban seats any more. In our most expensive cities this group will often have high incomes, and consider themselves middle class, but still be insecure financially. This has contributed to the myth of the Wealthy Liberal Metropolitan Elite. In practice older homeowners in places like London and Manchester still trend Tory but young graduates who can’t buy a house very much do not.

What’s really interesting is what happens as this group, increasing in size due to the expansion of higher education, gets older. First it’s taking longer for them to get to economic security both because of housing, and because their parents are living longer and not downsizing. High house prices and generous inheritance tax rules do lead to generational wealth transfers but often not until people are in their late 50s or early 60s. (Of course plenty of graduates are not in line to inherit and vice versa with non-graduates but there’s a correlation.)

Secondly, even when they do move into a position of security they are more socially liberal than their parents generation, more likely to have voted Remain, and have probably been voting Labour or Liberal for quite a while. So will they shift Tory? (A question Stephen Bush also looked at in the FT).

At the moment the signs are this group are staying more aligned with progressive parties even as they get on to the property ladder. If you look at wealthy constituencies such as Wimbledon/Carshaltan/Esher/Twickenham and Richmond Park in the South-West London/Surrey cluster; they have either moved Liberal Democrat or will likely do at the next election. These places have well above average numbers of high income families with children. But whether because of Brexit, dislike of socially conservative rhetoric, or simply out of habit, they are not voting Tory.

In previous generations the drift of well-off middle aged people to commuter suburbs has not affected their typically solid Tory voting patterns. But now it really is starting to. And the Tories are in danger of losing dozens of this type of seat next time. (Not just around London – Cheadle and Hazel Grove in Greater Manchester will also very likely go Lib Dem.) This problem for the Conservatives is exacerbated by the move to more hybrid working, allowing higher earners to move further away from cities, which may partly explain their oddly intense antipathy to working from home.

The pincer risk

That there is a realignment going on in British politics is well acknowledged. And there really is – at the next election the Tories are more likely to lose Wokingham than Bassetlaw. But it’s not quite the realignment that some commentators, and many Tory backbenchers, seem to think. We are not seeing a swathe of young, disillusioned, working class voters choosing the Tories in the hope their communities will be levelled up. What we have seen is older homeowners, in seats which had an historic attachment to Labour, choosing to vote for the party that delivered Brexit. At the same time younger professionals have been drifting to progressive parties both due to growing social liberalism but also their longer journey to economic security.

This model of realignment creates a real possibility that the Tories will be caught in a pincer movement. There are a large number of marginals that have a high number of increasingly economically insecure, Leave supporting, socially conservative, non-graduate voters. This includes much of the red wall but also many others constituencies in the middle England towns that are often neglected in political analysis but hold the key to a Parliamentary majority. As economic stagnation starts to bite this group are getting increasingly annoyed with the Government and are more prepared to go back to Labour. Especially if Labour can avoid jumping into the various culture war traps that the Tories, and their media allies, are setting. If Starmer and his team focus relentlessly on the economy and the NHS they could make significant progress here.

At the same time the socially conservative messaging on, say the Rwandan deportation policy or the BBC, that the Tories are pushing to try and hold this group, is alienating the young professionals in commuter-land who are reaching economic security. In these seats the Lib Dems can happily bang on about integrity in politics, the environment and so on, while not scaring anyone by proposing overly socialist-sounding economic policies.

This leaves the Tories caught between a Cameroonian strategy of capitalism with a friendly face (essentially what Jeremy Hunt would try if he became leader); and full blown Le Pen style populism. There is a way through this – which would involve a strong focus on green economic growth, while making a big pitch on the NHS and crime, and playing down the culture war stuff. You can see regional politicians like Andy Street in the West Midlands applying this model effectively. But it’s not clear there’s anyone in the national party that gets it. If that’s right, and Labour play their cards right, the Tories could find realignment ends up being a very painful experience.

Some thoughts:

1. I very much agree realignment is tough for political parties. All political coaltions have different, sometimes conflicting, interests, but there does tend to be a broad consensus on what takes priority. That's clearly been towards fiscal conservatism and markets in the Conservative party since Thatcher, and any shift from that is clearly going to be difficult for some to accept.

2. I'm not sure "social conservatism" is really the right descriptor for the instincts of the hypothetical average low income voter in Thurrock. Ed West discusses this a bit more fully here (https://unherd.com/2021/02/are-you-a-basic-conservative/) - you wouldn't expect them to respond to a campaign on pornography/marriage/abortion/gambling/alcohol. I think the better framework to look through is the one Sir Paul Collier sets out in "The Future of Capitalism" - in summary that those who are poorer, and lacking in status, tend to put more of their identity into their nationality, while the typical successful graduate puts increasingly less (Brexit has probably supercharged this effect in the UK).

3. The Lib Dems have (probably not intentionally) become a party representing and challenging in almost exclusively richer seats, especially in the South East. This might mean they can offer a social and economic way of thinking that is very effectively targeted to them that neither of the two main parties can.

4. Neither Labour nor the Conservatives seems to have a confident explanation of how they are going to manage these new groups and interests that will be increasingly key players in mid-21st century UK politics. The main difficulty to doing so being that at present the older vote is still very strong - it's big, it turns out, and it's geographically efficient (to the point where you could win most other groups at half-decent margins and still lose).

Where does this leave the Lib Dems? Targeting the leafy outer suburbs and large parts of the home counties should give them more MPs and be more efficient (re votes per seats gained) but they could then be split on issues such as planning, and do they make much of an effort in other parts of the country?