We have a guest post today from Ed Balls and Dan Turner. Ed won’t need much introduction to our UK readers - he was a senior adviser to Chancellor Gordon Brown before becoming an MP, cabinet minister and then Shadow Chancellor. He is now a Professor of Political Economy at King’s College London and a Senior Fellow at the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government at the Harvard Kennedy School. He also presents ITV’s Good Morning Britain.

Dan is an honorary research fellow at the University of Sheffield and a former Frank Knox Memorial Fellow at Harvard University.

This post covers research Ed and Dan have done on the strengths and weaknesses of “Bidenomics” and looks at what the UK can learn from their findings.

Two years ago, in a speech to the Peterson Institute in Washington DC, then-Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves released a new portmanteau into the world: “securonomics”. In that speech and the accompanying Labour Together pamphlet, she drew explicit inspiration from the US Biden administration’s ‘modern supply side economics’.

Some of the themes of her speech have carried over into the Treasury (witness the talk of ‘active government’ in March’s Spring Statement). But the self-conscious emulation of President Biden’s economic policy has been quietly dropped. Which makes political sense: following the Democratic Party’s 2024 presidential election defeat, most commentators have sought to pin the blame on the outgoing administration’s economic record.

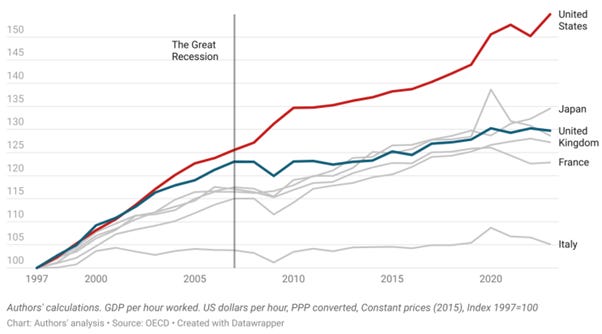

But has the new government moved on too quickly? After all, Reeves singled out the US economy for good reason: it delivered the fastest growth in the developed world (see figure 1 below), with the benefits going disproportionately to lower wage earners, while seeming to pull off an elusive “soft landing” following the post-pandemic inflationary surge.

Figure 1: Not just bluster: the US grew 4x faster than the UK in the five years since the pandemic

Last Autumn we set out to capture the immediate lessons from the Biden administration’s economic policy in our latest Harvard-Kings working paper. Alongside our co-authors Huw Spencer, Julia Pamilih and Vidit Doshi, we spoke to fifteen leading US economists, inside and outside the White House, including five former Council of Economic Advisers members (three of them former Chairs); four former National Economic Council Directors, and two former Cabinet members. You’ll see some of their names and quotations pulled out below in the analysis below, and we have published all fifteen interviews here too.

Below, we set out our four conclusions from the US, and our thoughts on what it means for the Chancellor today.

Conclusion 1: Our interviewees differ on whether the political cost of the American Rescue Plan’s inflationary impact outweighed the economic gains of stronger jobs and productivity growth. They fundamentally agree that the US would have faced inflation regardless and that, in retrospect, fiscal policy added to the high rate of inflation.

The $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan (ARP), passed under President Biden in 2021, is the most criticised element of his economic agenda. Jason Furman told us, “I have no doubt… that the American Rescue Plan was too big”, while former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers described it as “an enormous mistake”.

But defenders, such as Council of Economic Advisers chair Jared Bernstein and member Heather Boushey, argued the role of the ARP is overstated. Lael Brainard, Biden’s second Director of the National Economic Council, concedes the ARP was too big while disagreeing with the critics on its overall legacy: “Yes, some elements weren't essential. Was it decisive in terms of inflation? No. Probably one to two percentage points at most on the price level. But it also supported a significantly earlier and stronger recovery in GDP and the labour market” as the visible recovery of the US labour market in 2021 below makes clear.

Figure 2: The US saw an exceptionally sharp increase in unemployment during the pandemic but quickly recovered

The more nuanced view inside the administration was that there was a trade-off to be made, between the risk of slightly higher prices or a slightly weaker recovery. As White House economists like Jonas Nahm (of the Council of Economic Advisers) put it, “We consciously made the choice that your eggs could be a little bit more expensive, but you’d have a job to pay for them.”

If we focus too much on the inflation story we risk learning the wrong lessons from the US. The overall size of the pandemic era-stimulus was actually similar between the UK and the US, as was the rise and fall of inflation; but our economy has, if anything, become even weaker since 2020 while the US economy has surged ahead (see figure 3, below). And, with demand faltering and energy price shocks fading, deflation is a more credible risk than inflation for the UK.

Figure 3: The US economy surged further ahead of the rest of the G7 after 2020

Conclusion 2: What was really distinctive about the US under Biden was not its inflationary surge, but its dynamism: a resurgent “creative destruction” in the economy which the UK missed out on.

Public debate often misses the most distinctive aspect of the US economic recovery: its remarkable dynamism. A period of intensive “creative destruction” was driven by two choices: running the economy ‘hot’, with an emphasis on full employment; and enabling a huge reallocation of labour (the so called “Great Resignation”).

The scale of the US fiscal response to the COVID-19 pandemic was unprecedented in the US. The stimulus totalled roughly 25% of GDP ($5.2 trillion), exceeding any other major economy's intervention.1 By comparison, the stimulus during the Great Recession was approximately 7% of GDP, and only 0.9% during the Dot-Com bust.2

But the stimulus was designed differently. The UK deployed a whole host of guarantees, loans and equity investments to keep firms afloat, alongside the furlough scheme to keep workers tied to jobs. By contrast, in the US firms were allowed to collapse and unemployment to spike - reaching a peak of 14.8%.

Figure 4: Job destruction and creation surged in the US (in 2020/21 and 2021/22 respectively), returning to pre-financial crisis levels – unlike the UK

As a result, around 15% of the US workforce switched employment in the aftermath of the pandemic, especially workers in poorly paid service industry jobs who were typically moving to better managed, better paid, more productive employers.3 Long-standing labour market inequalities for women, Black and Hispanic workers and young people saw their decline accelerated.4

This was an accident. Those we spoke to in the White House wanted to do more to keep people in their jobs, but were held back by the weakness of the US welfare system and an inability to respond as rapidly as the hyper-centralised UK (where furlough was designed and implemented within days).

But the disruption, coupled with a surging safety net of pandemic-era benefits targeting households rather than firms and jobs, served the US well. Larry Summers summarised the lesson for us: “the fact that America permits more creative destruction, and as a consequence enjoys more creation… is probably the lesson from the recovery.” Jared Bernstein added that “If it’s true that to get on a higher productivity growth path you have to experience some economic disruption and pain – and I think it might be – the solution is to make sure you have a healthy social safety net”.

Conclusion 3: The productivity gap between the US and UK/Europe today pre-dates the Biden administration. It is primarily driven by the fundamental strengths of the US economy as a continent-wide knowledge economy and magnet for money and talent.

The productivity gap between the US and UK/Europe is long-standing. Looking back at figure 3, you can see that we’ve had moments, such as the 1990s and 2000s, when the gap begins to narrow off the back of strong UK growth. But it has been widening ever since the Global Financial Crisis.

Why the gap? It comes down to what Adam Posen (President of the Peterson Institute for International Economics) described as the “bigger forces” behind US strength, making it resilient to the lurches of policy between administrations: “The fact is the US can keep screwing itself up in unbelievable ways, but there’s some underlying thing that keeps us resilient. I don’t get it!”

These forces include the size of the US’ single market, the dominant global currency, a growing population driven by both immigration and (until recently) fertility, deep capital markets, an abundance of natural resources including energy, and a strong human capital base. They all contribute to the country's capacity for growth. Larry Summers told us that “it's the system more than the particular policies pursued in those years that I suspect deserves dominant credit”. Taken together, the strengths of this dynamic economy have meant that, in recent years, productivity growth has returned and even accelerated in the US – even as productivity has been stagnant in Britain and low in Europe for more than a decade:

Figure 5: Productivity growth is not just higher in the US than in Europe – it has started accelerating again since the mid-2010s

These ‘fundamentals’ are not all products of chance. The US government set the foundations for today’s tech sector through concerted spending on R&D and defence during WWII and the Cold War.5 The US’ divergent response to the financial crisis in 08/09, which included a much more considerable fiscal stimulus than the UK or Europe, plays a role in the strength of the relative US economy today; as does sustained high-skilled migration. And the US case shows us that there’s nothing inevitable about ever-declining productivity: policy choices could, plausibly, make a difference.

Conclusion 4: While the Biden administration adopted a more interventionist approach to the economy, the tools used were not unprecedented (even in the US). The scale of the industrial policy ambition was novel, but given the results of the Presidential election we are unlikely to ever definitively know what its full impact might have been.

As Rachel Reeves recognised, ‘Bidenomics’ opened the political space for a broader economic policy toolkit in the US and Europe, with a larger role for the state in driving higher productivity growth. It was never intended to be a “one term project”, and advocates argue that it is too early to assess the full impact of Biden era economic activism. But our interviewees do highlight some emerging lessons.

I. Industrial policy was not new, but the scale of it was.

Industrial policy – directing the productive capacity of the US economy towards strategic objectives – was a central pillar of Biden’s microeconomic agenda. It is the policy that advocates reach for when confronted with the inflation debate, as the ‘genuine’ preoccupation of the administration.

As Biden’s first director of the National Economic Council, Brian Deese told us, “the core theory behind the Biden industrial strategy wasn’t unprecedented…it was just more ambitious and more unapologetic than prior efforts”.

Figure 6: US manufacturing construction spending surged as Biden’s flagship legislation passed in 2022 (before falling after Trump’s election in late 2024)

Our interviewees offered several lessons for effective industrial policy. First, avoid picking winners: the government should use tax credits and debt financing rather than grants, where possible. Tax credits put the onus of innovation on firms: “Private companies have to figure out which of these tax credits made certain activities viable and profitable. And then the private sector would be entrepreneurial about where to invest. We weren't choosing” (Lael Brainard). Senior adviser to President Biden, Gene Sperling backed policies that “don’t force you to pick individual winners but just set criteria…Those give the entire field incentives to aim higher.” And Government needs an exit plan: identifying “where [industrial policy] ends and when the training wheels come off”, as Jared Bernstein put it.

Beyond avoiding picking winners, governments must ensure that they create open competition within sectors. Heather Boushey told us “you really have to pair industrial policy with antitrust to make sure you’re not left with just one national champion.” And Brian Deese said that clarity over goals is necessary to avoid corporate capture: “The clearer the goal – and the clearer the public debate around the national and economic security priorities – the better.”

II. Place-based partnerships and strategic funding represents a new US approach to dealing with economically left behind communities.

Place-based policy under Biden was more innovative than previous US initiatives.6 A major tool was the Regional Challenge programme – from Build Back Better to National Science Foundation Engines to Tech Hubs – which distributed millions of dollars in targeted grants to winning regional coalitions of local governments and business groups, comparable to England’s new Combined Authorities. This was new for the US (even if it’s more familiar to European audiences) and required a big surge in spending: the US Economic Development Administration budget went “from $400 million to $6.8 billion”.

III. Retaining – or expanding – broad-based protectionism has a weak economic logic and should be firmly scrutinised when justified on other grounds. Proposals to protect strategic industry require a clear economic or security rationale.

Arguments around national security and reindustrialisation were used by the Biden administration to justify the continuation of Trump-era tariffs and barriers to trade. Lael Brainard underlined the dominance of China in certain sectors as a motivating factor in the administration’s approach to manufacturing: “There was fundamental concern about any area where China would have 90% share. We felt that Europe was not sufficiently attuned to those risks and should have worked with us more on that.”

But even some sympathetic interviewees at times think the retention (or in some cases extension) of Trump-era barriers to trade went too far. Jonas Nahm told us: “[it] would have been easier to make [principled arguments for protecting certain sectors] if Biden had taken some of the tariffs away that were really unrelated to reshoring – we’re never going to make baby clothes and Christmas lights in the US, so why do we have tariffs on them?”

For many of our interviewees, broadbrush protectionism inhibited progress on Biden’s other goals, rather than enabling it. Jason Furman reflected that “There’s a big difference between installing solar panels in the US, which I wholeheartedly support, and making solar panels in the US, which, if it means more expensive, lower-quality products, I’m not on board with”. Adam Posen put it most forcefully, telling us that “the end result of [protectionism] is that the green transition has slowed because we don't have cheap solar panels. The rest of the world also doesn't have cheap solar panels because we're making them harder to get from China.” And Biden-era choices have left global institutions in a weaker position to manage Trump, as he continued Trump’s 2019 decision to block appointments to the World Trade Organization’s Appellate Body (the “supreme court” of world trade).

Making Bidenomics Great Again: Lessons for the UK

Every country faces its own challenges, and the world is very different today compared to five years ago. But perhaps the comparison between the UK in 2025 and the US in 2020 isn’t as strained as first meets the eye: in both cases new, centre-left governments inherited a technology-driven economy from predecessors who had cut back on the role of the state in economic policy and thrown up barriers to trade. Both were grappling with the long-run challenges of bringing growth back to “left behind” communities, and with acute challenges in keeping the economy moving in the face of shocks to global supply chains.

The differences are just as important. The US economy Biden inherited was already strong, even if the inequalities it contained - across place, race and class - are more pervasive and persistent than in the UK. And the US enjoys the exorbitant privilege of extensive, cheap credit which the UK decisively lacks (especially after Truss’ mini-Budget). On the other side of the ledger, the UK has a more decisive political system capable (if the government of the day wants it) of legislating in a way White House teams can only dream of.

What do our conclusions about the US mean for the UK today?

First, do what you can to “run the economy hot”. If the broader benefits of full employment for inclusive growth are clear – in job creation, dynamism, and wage compression in favour of the lowest earners – then the government should support strong demand growth (consistent with anchored inflation expectations and credible borrowing plans). The important thing is that we don’t over-correct from the Biden-era inflation surge, becoming so scared of inflation that we risk the opposite problem of stagnation and unemployment.

But running the economy hot only delivers if you pair it with more dynamism. The advantage of a “hot” economy is that it gives businesses the confidence to invest to meet expanding demand, and it gives workers the leverage to negotiate better terms or to move jobs. Flexibility and dynamism can be powerful tools for expanding opportunity, raising productivity and supporting upward mobility. The UK needs to avoid introducing new rigidities into its labour market. As the government thinks through how to respond to ongoing consultations around its Plan to Make Work Pay, they should focus efforts on introducing a more effective insurance scheme that provides workers the time and support needed for more productive reallocation of the workforce. At the moment, the UK has the lowest unemployment insurance replacement rate (the typical share of your pre-unemployment income replaced by benefits) in Europe, creating a strong disincentive to risk leaving a job.

Figure 7: the UK has the least generous (non-housing) unemployment benefits in Europe

We can raise underlying growth through trade and innovation-led growth… The UK should use the forthcoming Spending Review to support and expand areas of economic strength (universities, tech, knowledge-intensive services and life sciences). And, unlike the US, we need the scale economies that comes from access to global markets. Given proximity and that 42% of the UK’s exports go to the EU (compared to 21% for the US or 2% to India), our view is that the government should begin by revisiting UK-EU trade arrangements, to strike a new deal to remove trade barriers and deepen engagement.

…and we should do so everywhere. So far so orthodox. But, as our previous work alongside MIT’s Anna Stansbury on the drivers of UK regional inequalities makes clear, that should not mean backing the Golden Triangle of London, Oxford and Cambridge to the exclusion of other regional economies. The UK has some of the weakest agglomeration effects in the OECD – that is, cities don’t bring the productivity premium that other countries observe. There is no inherent reason the UK’s city-regional economies cannot be as productive as their equivalents in France. We calculated last year that fixing transport in our non-Southern cities and raising their skills profiles up to the national average would raise GDP by £55bn – even before we take steps to boost innovation-led business.

The “modern supply-side economics” toolkit can drive growth in priority sectors; but should only be used if its closely tied to pro-competition reform, taking on vested interests. We think the Government is right to be ambitious in using the forthcoming Industrial Strategy and Spending Review to aim to tackle particular bottlenecks and solve coordination problems in priority growth sectors. The overall spending on “industrial policy” measures in the US, through flagship Biden-era legislation, amounted to about 0.5% of GDP per year: substantial, but not unaffordable. The smaller size of the UK economy means we will need to prioritise (sub-)sectors more than the US, but we can afford US levels of ambition.

Agencies like the National Wealth Fund should have a range of tools to deliver – from loans and guarantees to equity investments in promising young firms – and, like their peers in France (Bpifrance) and Germany (KfW) should have the ability to borrow directly from markets to meet their missions. Government should also be prepared to use the national tax system to shape investment, as is already the case with the R&D tax credits introduced by the last Labour government.

But priming the fiscal pumps won’t work if there aren’t good investments to back across the country. Identifying and plugging gaps requires local expertise and delivery know-how, so it cannot be delivered by Whitehall: it needs strong Mayoral Combined Authorities, with more staff than they currently have, to deliver.

And finally, all of the worst forms of industrial policy are more likely when we don’t have the dynamism or macroeconomic growth we call for above – so proceed with caution. There is a tension between industrial policy and pro-competition policy, but it can be managed provided both are pursued rigorously. That means properly funding industrial policy on the one hand, while continuing to champion free trade and contestable markets with the other. The right approach is to focus on a tight list of priorities, using tax credits, loans and guarantees alongside a robust pro-competition policy to drive private sector investment while safeguarding against political capture.

The elephant in the room is that Bidenomics also shows us that effective policy execution, especially in the face of global economic headwinds, is not enough. (Though it is necessary: Heather Boushey told that “If you aren’t creating good jobs, it’s hard to get across the [political] finish line. [But] If you are, you still need to figure out everything else”.)

That demands a narrative around the government’s growth plans and the UK’s economic future, rather than risking “completely talking past people on the economy” (as Jared Bernstein put it on the US under Biden).

All of these policy choices – reopening trade conversations; developing land around innovation clusters; making the case for skilled migration (including student numbers and those with STEM skills) - will come at the cost of political capital. But without finding and communicating an economic narrative, the government risks allowing the economic argument to be set by the opposition – as the Democrats found out to their detriment in the 2024 election.

Dean, P. (2022). The Unprecedented Federal Fiscal Policy Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Impact on State Budgets. California Journal of Politics and Policy, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.5070/P2CJPP14157320

Ibid.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. (2022, May). Economic well-being of U.S. households in 2021 (Report). https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/2021-report-economic-well-being-us-households-202205.pdf

Autor, D., Dube, A., & McGrew, A. (2023). The unexpected compression: Competition at work in the low wage labor market (NBER Working Paper No. 31010). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w31010

Gross, D. P., & Sampat, B. N. (2023). America, jump-started: World War II R&D and the takeoff of the US innovation system. American Economic Review, 113(12), 3323–3356.

Hanson, G. H., Rodrik, D., & Sandhu, R. (2025). The US Place-Based Policy Supply Chain (Working Paper No. 33511). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w33511

Biden definitely could have done more to make ordinary folk feel the economic benefits to a greater extent.

But I do think there is an issue in that the idea that left-leaning politicians are “bad” at economics/fiscal policy and that right-leaning ones are “good” at it, is just hard coded into public and media consciousness.

Centre-left govts that are doing good stuff economically never seem to get any credit and when the slightest thing goes wrong it’s all “socialists who’ve never run a business before can’t run an economy brrrrr”.

Meanwhile people just assume centre-right politicians will do a better job even when they are being quite incompetent. And when things go wrong the media always seems to point to extraneous factors.

If Truss/Kwarteng had been Labour we’d hear no end of it. It’d still be making headlines in the right-wing press. Nick Robinson would bring it up in every interview. Blokes in pubs would be bringing it up as a reason not to trust the left well into the 2050s.

In reality it now seems to have disappeared from public discourse even though it was quite a remarkable event that is still having impacts on us today.

Ed Balls