Realignment Realigned: The Local Elections Review

When I pressed send on last week’s preview I was a bit nervous as my predictions were significantly more bearish for the Tories than most. Was I being too pessimistic about their chances and conversely, too positive, about the Lib Dems and Greens in particular?

It turns out I wasn’t bearish enough. My estimate for the national vote share was pretty close. I predicted:

Lab 38%

Con 26%

Libs 18%

Others 18%

And the result according to the BBC is

Lab 35%

Con 26%

Libs 20%

Others 20%

But I underestimated the degree of tactical voting which has led to even worse results in terms of council and seat losses for the Tories than even I had anticipated. My prediction for councils was:

Lab 61 (+12)

Con 43 (-38)

LD 20 (+3)

Green 1 (+1)

NOC or Independent 105 (+22)

The results were:

Lab 71 (+22)

Con 33 (-48)

LD 29 (+12)

Green 1 (+1)

NOC or Independent 96 (+13)

In terms of seats I said 1000 Tory losses wouldn’t surprise me but my mid-point was 850-900. They actually lost 1,061. I thought Labour might gain around 700, they got 536, as they’re vote share was a bit lower than I expected. But they gained more councils which shows very effective targeting. I also said they’d become the largest party in local government for the first time since 2003, which they did. The Lib Dems and Greens did incredibly well, picking up 405 and 241 additional seats respectively.

Interpreting the results

I had anticipated that the Libs and Greens would do better than polling was suggesting for two main reasons. First, more tactical voting, given the strength of the “time for a change” anti-Tory sentiment, and with the threat of Corbyn gone. Secondly, the ongoing demographic shift out of London which is seeding the home counties with younger, more liberal voters. Both had an even more dramatic impact than expected.

Tactical voting was most evident in Bracknell Forest where Labour and Lib Dems didn’t stand against each other and took 27 seats off the Tories. Labour took control having only previously had four councillors. In other areas there was more sutble collusion. But even without this direct guidance from the parties, voters, in seat after seat, identified the party most likely to beat the Tories and backed them. Thus mid-Suffolk became the first Green controlled council in history and the Lib Dems picked up huge numbers of seats to take councils in places like Stratford-upon-Avon and Windsor and Maidenhead. In both cases I though the Tories would lose control but not that the Libs would take it. As Ed Davey excitedly noted Windsor Castle (and Eton school) are now in a Lib Dem ward.

On the second point about demographic shift, results in Hertfordshire demonstrated how rapidly some of the home counties are moving away from the Tories. I thought they would make losses in both East Herts and Hertsmere but did not expect them to lose control of both councils. As recently as 2015 the Tories held all 50 seats in East Herts and now they have only 16, behind the Green Party. It raises big questions for the party even in the short term, let along the long, about a whole sweep of Westminster seats that have been Tory forever. Grant Shapps is looking vulnerable in Welwyn Hatfield. As does Bim Afolami in Hitchin and Harpenden. And even MPs that look, on paper, extremely safe like Mike Penning in Hemel Hempstead and Oliver Dowden in Hertsmere will be getting nervous. We saw similar patterns in Surrey, Kent, Sussex, Oxfordshire, and Berkshire.

There have been some suggestions that, even if things were clearly worse for the Tories, Labour should also be disappointed with the results. They did do a bit worse in their national share than I had expected. But look where those votes went, not to the Tories but to other “progressive” parties (I dislike the word “progressive” in this context, especially given how big a role nimby-ism played in many contests, but all the alternative synonyms are too wordy).

It is true that in the 1995 locals, prior to Blair’s 1997 landslide, Labour got a 47% share of the vote, compared to 35% now. But the Tories were in almost exactly the same place on 25%. The difference now is a much bigger share of the anti-Tory vote is going to the Green party and independents. The main shift between 1995 and 2023 is in the distribution of the anti-Tory vote, not its existence. Sunak is in just as bad a position as Major was then, and without even a once-in-a-generation political talent like Blair to blame it on.

Tory strategists might counter that in the 2013 locals the Tories also only got 25%, so there’s reason to hope for a similar comeback. But the critical difference then was that UKIP won 22% of the vote. There was a chance to unify the right, which happened across the 2015-2019 general elections. Now the Tories are getting 26% but there is no vote on the right to squeeze. UKIP are done, they lost their final few seats, and Reform only stood in a small number of places. Nearly all the remaining three quarters of the vote is to their left (bar a handful of independent groups in places like Boston and Castle Point who are definitely not). And demographics trends are continuing to move away from them.

There remains uncertainty as to whether Starmer can win a majority. But one thing we can be sure of is that if Labour, Lib Dems and Greens are collectively getting 65%+ of the vote, as they did this week, there is absolutely no route to Sunak retaining the premiership.

Of course this large progressive bloc will not act in an entirely efficient way come general election time, given out first past the post system. Not every local Green or LD voter in a Tory/Labour Westminster marginal will switch, but many will. And the overriding story of these locals is this coalescing anti-Tory vote behaving in a much more efficient manner than at any point since 2001. Labour won where they needed to in places like Medway, Gravesham, Dover, Stoke, Hartlepool and Swindon, and lent votes to other parties where they didn’t. There were a couple of target seat disappointments like Peterborough and Stockton, but such exceptions were rare. If you’d shown any analyst this set of results and asked them to guess Labour’s vote share they’d have gone for a figure higher than 35%.

We also saw the Libs triumph in all their targets bar East Cambridgeshire (due to dislike of their local congestion charge), despite their Westminster polling being only marginally better than 2019. This concerted pincer movement on their seats represents serious danger for the Tories. And it is not just a consequence of tactical voting but of a Tory strategy that has got them stuck between different demographics, pleasing neither. I wrote about this a year ago in a piece called “the real realignment”, and I think it’s held up well:

“There is a real possibility that the Tories will be caught in a pincer movement. There are a large number of marginals that have a high number of increasingly economically insecure, Leave supporting, socially conservative, non-graduate voters. This includes much of the red wall but also many others constituencies in the middle England towns that are often neglected in political analysis but hold the key to a Parliamentary majority. As economic stagnation starts to bite this group are getting increasingly annoyed with the Government and are more prepared to go back to Labour. Especially if Labour can avoid jumping into the various culture war traps that the Tories, and their media allies, are setting. If Starmer and his team focus relentlessly on the economy and the NHS they could make significant progress here.

At the same time the socially conservative messaging on, say the Rwandan deportation policy or the BBC, that the Tories are pushing to try and hold this group, is alienating the young professionals in commuter-land who are reaching economic security. In these seats the Lib Dems can happily bang on about integrity in politics, the environment and so on, while not scaring anyone by proposing overly socialist-sounding economic policies.”

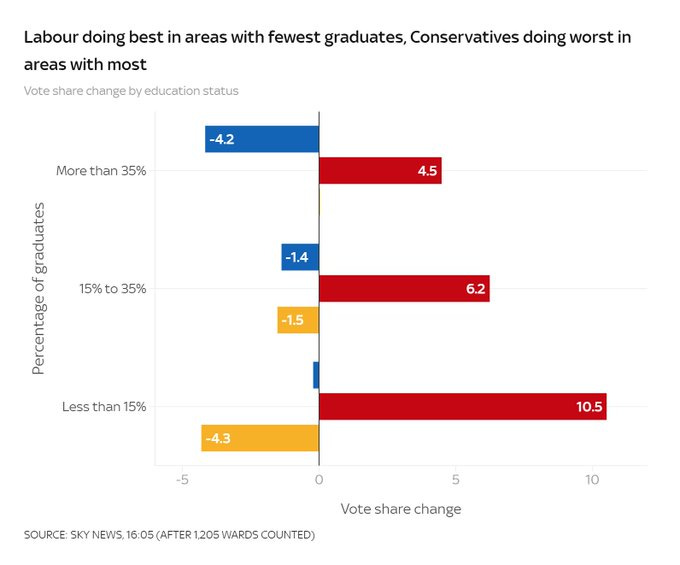

This is what we saw yesterday. As Will Jennings showed in his analysis for Sky, Labour did best in areas with fewer graduates, exactly the sort of seats which moved away from them during the Brexit/Corbyn era. But the Tories did worst in the seats with the most graduates, repelled by their continued forays into populism.

Where does the narrative go next?

These results should be the end of the rather desperate “Sunak comeback” narrative that’s been heavily pushed by the Tory-friendly press in recent weeks. It was always overdone. After all he could hardly not make some improvements after the lows of the Truss debacle. But the party is still in a dire state. While he is more popular than post-partygate Johnson or Truss he remains less popular than Starmer. Meanwhile as I discussed in this piece the Tory brand “is so far down the toilet it’s disappeared beyond the u-bend.” In recent weeks the limited poll narrowing we had been seeing in previous months has stopped, which will make that narrative even harder to sustain.

This is not really Sunak’s fault. I disagree with some elements of his strategy but he took over a broken party in an impossible context. As FT columnist Robert Shrimsley puts it:

“For the past three months, Tories have been allowing themselves to believe that under Rishi Sunak the mere restoration of floor-level competence and political sanity would be enough to reverse the electoral tide. These elections present a timely dose of reality for those who were getting dizzy with the novelty of a capable prime minister.”

“It’s the economy stupid” has become one of the most common cliches of political analysis since Bill Clinton’s campaign manager, James Carville, stuck in up in the 1992 campaign war room to remind colleagues of their key messages. But his other two messages are less well known: “don’t forget health care” and “change vs more of the same”. With the economy and the NHS voters’ top two priorities by miles, and a strong “change” mood after 13 years of Tory government, Labour, and other opposition parties, are in the rare position of being able to run strongly on all three messages. Given that, it’s very hard to see how the Conservatives can possibly survive in government next year, beyond a miraculous economic turnaround.

The only good news for Sunak is that, in the absence of any viable alternative leadership candidates, he is safe until the election. The more self-aware Tory MPs feel increasingly resigned to their fate. I suspect many more will stand down over the coming months, or scramble for one of the safer new seats created by the boundary review.

While, no doubt, some Tory-leaning commentators will want to keep hope of an unlikely majority alive, and promote various hypotheses to explain how it might happen, I suspect media attention will increasingly shift to Labour. The new narrative will be that while the Tories are almost certainly going to lose, and badly, Labour may not be doing enough to win a majority. Back to my is it 2010 in reverse question again?

In some ways this isn’t as important a question as it may seem. A Starmer minority government, backed by a Lib Dem contigent of 30-40 MPs, would not necessarily be that much less powerful than one with a majority. It’s hard to think of many scenarios in which it would be in the Lib Dems interest to vote with the Tories on a no confidence motion – even if there is no formal coalition or confidence and supply deal. One big issue on which it would make a negative difference is planning and housebuilding, as Starmer is starting to promise serious action here which the Lib Dems would struggle to support given the importance to their vote of being able to block developments. Elsewhere, though, it could improve governance if Labour has to persuade other, relatively like-minded parties, of the benefits of legislation before ramming it through.

Nevertheless Starmer will, of course, want a majority. It would make life easier for him and remove the risk of a tactical no confidence vote from smaller parties. With impeccable timing I have a new podcast exploring this question starting next week. It is called “The Power Test” and aims to answer this question of what Labour need to do to secure a majority but also, more importantly, what policies they should be pursuing in order to make the country better. It will be co-hosted with the brilliant Ayesha Hazarika, former Labour party adviser to a string of leaders, and now broadcaster with Times Radio and columnist for the Evening Standard. Our first guests will be Alastair Campbell and Claire Ainsley, Starmer’s former policy chief. You will be able to download from your favourite podcast platform. Listen to the trailer here.

In the first episode we’ll be discussing with our guests what they make of these results; whether they agree with me that there is vanishingly little prospect of a Tory government; how important a majority is for Labour; and what they should do if they get one.

You do wonder, with the voter ID thing, if the Tories have hit inadvertently on a selection advantage for the Lib Dems.

I think, certainly for mayoral elections, all the opposition parties should insist on a change back to a preferential system. Electing someone with significant executive power on a third of the vote doesn’t lead to policy making with community consensus

.. apologies for precipitate comment .. I’ll be brief ...

.. inadequate lense through which to observe the problems of the NHS.

Lots of people won’t like this - including many from my ‘tribe’ on the liberal centre left - but we have to be willing to contemplate new models for the national health service. But I see no signs of Starmer’s getting a grip on this.

There is a general acceptance at senior levels of the NHS & the medical establishment generally that the government is set on privatising the NHS by one means it another.

We are training doctors and nurses but not giving them enough hands on supervision in their early careers. Consultants are absent doing private work. Clinical decisions are woefully slow and risk averse as a result. Triage rates in A&E speed up tenfold when consultants step into the trenches.

Nurses are ill served by the move from bursaries and nursing college to university & debt.

On the shop (hospital) floor staff are undermanaged and allowed to forget that they should be driven by their caring vocation not by employment demarcation. This is partly to blame for the fact that patients are routinely left unhydrated or in soiled linen.

Procurement practices, hospital food, and lack of adoption of successful /

best practices elsewhere in the service are all a disgrace.

I’m as keen as anyone on seeing nurses and junior doctors well (better) paid, but this won’t on its own make the service better or safer.

The NHS needs root and branch rethinking- and not by politicians.

I strongly advocate the establishment by the next Labour government of a Royal Commission with a brief to propose the best way forward disregarding politics and dogma, and preferably setting it on course to be operationally independent of governments.