This is the third of my three pieces marking the 20th anniversary of the start of the Iraq War. For seven years I served as a member of the Iraq Inquiry and so this piece draws on the Inquiry’s work and conclusions, but these are my personal reflections.

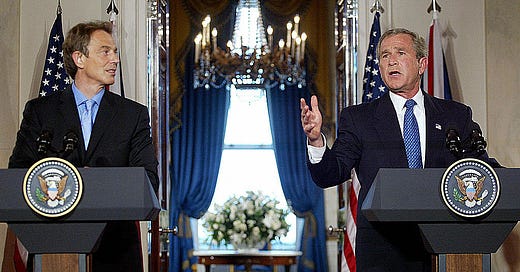

In my first piece I considered why the intelligence assessments on weapons of mass destruction (WMD) took the form they did and how the government became invested in them when they should have been questioning. In the second I discussed the role of the military in pushing for a prominent army contribution in the first phases of fighting while seeking to avoid one in the occupation of Iraq. In this third post I consider why Tony Blair decided to join the US in the war though UN inspectors had not completed their work assessing the state of Iraq’s WMD and why so little preparation had been made to cope with the war’s aftermath.

The Impact of Kosovo

The origins of the decision lie in Blair’s relative success in his first five years as Prime Minister in the foreign policy field. Particularly influential was his experience with his first big crisis – the Kosovo War which lasted from March to June 1999. Slobodan Milosevic, leader of what was by now a rump Yugoslavia after Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia had all gone their own ways, was a Serb nationalist who had been suppressing the province of Kosovo (not a separate republic so without the right to go its own way) since the 1980s. As resistance grew among the Kosovars to rule from Belgrade, Milosevic clamped down, creating a major humanitarian crisis. After he agreed to show restraint in late 1998 the crisis flared up again the next March. To bring him back into line, NATO agreed to what was expected to be a short bombing campaign. In the event it took three fraught months to reach a satisfactory conclusion.

Although the Americans were responsible for the bulk of the air campaign, Blair took the lead as it became more controversial, in not only urging that NATO stayed the course but insisting that it prepare to use land forces, offering a leading role for the British army. After Milosevic capitulated this was seen as a success for Blair, which gave him confidence in his foreign policy judgement.

Watching President Bill Clinton deal with the domestic resistance in the US to this sort of operation, he was left concerned about whether the US would be willing in the future to engage with European crises. This concern that the US was becoming more isolationist was reinforced by George W Bush’s success in the 2000 Presidential election on a platform that suggested that US military power should be saved only for the big wars.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Comment is Freed to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.