A few weeks ago, during a rare lecture to undergraduates at King’s College, I started to talk about the 2003 Iraq War. I soon realised that all this had happened before most of my audience was born. It has become old news, even though its consequences are still being felt, especially in the Middle East. We are now coming up to the 20th anniversary, which is bound to lead to many reflections on the mistakes of that period, but also efforts to recall what happened and why it mattered.

I spent seven years of my life on the Iraq Inquiry, a body that is now also only dimly remembered (we published our report just after the Brexit referendum). I’m proud of the report, but I also have to acknowledge that it is extremely long. Only the most curious citizens and dedicated researchers will turn to it to refresh their memories. I’m therefore going to offer some thoughts about those events in a series of posts for Comment is Freed, highlighting issues raised by the war and addressed in the report (although I am now only speaking for myself).

First, in this essay I’ll look at the intelligence issues. For the second piece I’ll consider why the UK’s military contribution took the form it did, and lastly, closer to the anniversary, I’ll assess Tony Blair’s decision that the UK should join the US-led invasion of Iraq.

I’ve chosen to open with the intelligence issue because the experience of basing policy around a claim about another state’s intentions and capabilities that then turned out to be in error still informs public discourse. It casts its shadow every time the latest UK intelligence assessments are reported, as if because they were wrong two decades ago they are likely to be wrong now. This was evident in the debate surrounding the warnings issued by the US and UK intelligence communities a year ago about an imminent Russian attack on Ukraine, even though in this case they were correct.

It is also still widely assumed that the Labour government deliberately spread a false assessment about Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction to justify the war. This allegation has been disproved in every serious investigation, including that of the Iraq Inquiry. As I shall argue the only way that the government’s strategy in 2002-3 makes any sense is if the key players believed the assessment to be true. This not to exempt them from blame. The assessments suited their purposes and so they did not subject them to the necessary scrutiny, presenting them with far more confidence than they deserved. This was especially the case during the early months of 2003 when there were good reasons to start doubting their accuracy.

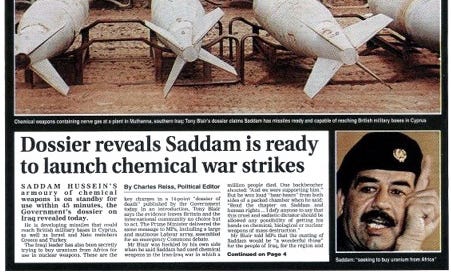

The main controversy centred on the publication of a dossier published by the government on 24 September 2002 and based on the assessments of the Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC). Although there was a positive precedent in a publication the previous year which provided the evidence about the Islamist terrorist group al Qaeda’s responsibility for the attacks on the US on 11 September 2001 (9/11), this dossier would be more detailed, getting into highly classified information. In the process it risked compromising the integrity and policy-neutrality of the JIC. A further complication was that the foreword by the Prime Minister, which was not prepared by the JIC, and which drew out the policy implications of the dossier, described the assessment as being ‘beyond doubt’, which it was not.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Comment is Freed to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.