Another bumper edition of the election briefing and I’m posting this one on the main site, and free to read, as I think today’s topic, Northern Ireland, is seriously undercovered in the British news media, despite being of great significance to all of us (as Brexit should, surely, by now have taught us).

The post is by Professor Jon Tonge of the University of Liverpool who has written extensively on Northern Irish politics, including co-authoring books on each of Northern Ireland’s main political parties.

As a treat at the end I’ve added in another batch of my seat previews, this time covering seven in Somerset.

Paying subscribers can get these election briefings every day during the campaign by turning on notifications for them on your “manage subscriptions” page. In the last few days alone we’ve had posts breaking down each of the MRP polls, and looking at the Reform “surge”, plus seat previews for Hampshire/Kent and Cornwall/Devon. I’ll be doing previews of every seat in the country over the course of the campaign.

You can become a paid subscriber here:

And buy a gift subscription here:

Oh and also a few people have asked if they can get signed or dedicated copies of my upcoming book. West End Lane Books have kindly agreed to facilitate this. You can order via this link.

More than just an intriguing sideshow: the general election in Northern Ireland

Welcome to the part of the UK having another a Brexit election, at least in its unionist constituencies. Welcome to the only part of Western Europe where religious background is the most important variable in how people vote. Welcome to Northern Ireland.

It is understandable if voters in Great Britain look upon Northern Ireland as an irrelevant sideshow. Labour does not stand. The Conservatives are fielding five candidates. The four who braved the contest last time managed 5,433 votes between them. It is doubtful whether Ed Davey will break the fun by paying much attention to the fortunes of his Northern Irish sister party, Alliance. No-one envisages the hung parliament that catapulted the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) to prominence as Theresa May’s only allies in 2017.

Yet if ‘marginal’ is the best description of the contest in Northern Ireland, that label also applies to many of its constituencies. Welcome also to the part of the UK with the highest percentage of slender majorities of under 3,000 votes.

The state-of-play

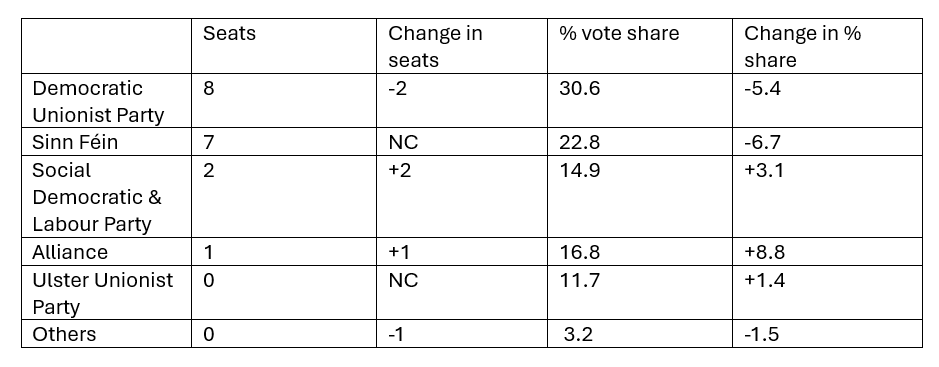

Reflecting how Northern Ireland is changing, the 2019 general election saw nationalist parties gain more seats than unionists (9-8, with one ‘other’ party, Alliance) for the first time, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 The 2019 general election in Northern Ireland

Notwithstanding some thawing, more of which later, polarised politics prevails. Have a look at Tables 2 and 3 if you think there is much crossover in a post-conflict polity. Table 2 indicates the percentages of Protestants and Catholics voting for the five largest parties. Table 3 shows the ideological breakdown of party voters, i.e. what percentage of each party’s voters self-identified as a unionist, a nationalist, or as neither unionist nor nationalist.

Table 2 Voting according to religious affiliation, 2019 general election in Northern Ireland

Table 3 Ideology and party voting, 2019 general election in Northern Ireland

As shown, Catholics and nationalists won’t touch unionist parties with a bargepole and Protestants and unionists heartily reciprocate regarding nationalist parties. Only the Alliance Party straddles the divide. Much of the election will see ancient inter-bloc rivalries affirmed and the constitutional question remains paramount: Northern Ireland in the UK versus a United Ireland.

Yet in only in a couple of constituencies, (Fermanagh & South Tyrone and North Belfast) are there tight Irish republican versus British unionist contests. In other parts, it’s the choice of party that unionists (especially) and nationalists make within their communal bloc that is crucial. So, what are these intra-bloc quarrels about?

Another Brexit election: the contest within unionism

Why still a Brexit election? At the risk of returning readers to horrors they thought consigned to history, Northern Ireland’s departure from the EU appears the most important faultline within unionist politics. Put simply, some unionists argue strongly Brexit was never really done for the region, which remains subject to many EU laws. Others are more sanguine.

Weeks before being charged with rape and other sex offences (charges he denies) the then DUP leader, Jeffrey Donaldson took his party back into the Northern Ireland Executive. The DUP’s walkout in 2022 had collapsed the Executive and the DUP also downed the Assembly.

The ‘Donaldson Deal’ to restore Stormont this year was sold by the DUP’s leadership as a huge triumph. It was claimed the package removed the border in the Irish Sea, which divided one part of the UK from another in economic and legal terms. Donaldson claimed checks on goods deemed at risk of entering the EU Single Market via Northern Ireland were gone.

Briefly it looked a DUP triumph. Northern Ireland’s largest party had removed the offensive aspects of the EU Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol, agreed by Boris Johnson and Taoiseach Leo Varadkar what might seem an eternity ago. Some of the Protocol’s trading impositions were replaced by the Windsor Framework, sold with boyish enthusiasm by Rishi Sunak. The DUP opposed both the Protocol and the Framework but hailed the revisions in the Safeguarding the Union document. A Lucid Talk poll indicated most DUP voters backed the return to Stormont. So far, so good.

Soon after, Donaldson’s unscheduled departure left his number two, Gavin Robinson, at the DUP helm. Having lauded the deal, Robinson now says that ‘cautious realism’ should have been the response. And behind Robinson, there was never enthusiasm anyway. Four of the DUP’s eight Westminster MPs thought the deal oversold and did not hide their scepticism.

Now, the DUP faces its toughest Westminster election in a generation. It’s been the largest Northern Ireland party at Westminster since its 2005 eclipse of the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), but Robinson’s outfit has several difficult constituency defences, none more than his own in East Belfast. Defeat could mean a new DUP leader. A recent poll put the DUP on only 21% across Northern Ireland, 10 points below its 2019 level.

Damage could be done by the Traditional Unionist Voice (TUV). Uncompromising, it implacably opposes any EU law operating in Northern Ireland and demands ‘No Sea Border’. Its leader, Jim Allister, was dismissed as a ‘dead-end unionist’ by the DUP’s Paul Givan when Stormont revived. Now, the TUV smells blood over the ‘overselling’ of (non-) revised arrangements and is standing in most constituencies.

Allister’s party will not win seats but a three-way TUV-UUP-DUP split in a declining unionist bloc vote - down 10 points from the 50% at the time of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement - could spell disaster for the DUP. Unionism could be left without a Westminster representative in Belfast.

To add to intra-unionist acrimony, the TUV announced an election pact with Reform UK earlier this year. The latter’s then leader, Richard Tice, addressed Allister’s party conference and demanded full Brexit for Northern Ireland. The memorandum became one of misunderstanding when Tice’s replacement, one Nigel Farage, promptly endorsed DUP candidates Ian Paisley and Sammy Wilson. Paisley is standing in North Antrim, against, er, Jim Allister.

Abstention and ambition: The contest within nationalism

Sinn Féin seeks to complete a hat-trick and become the largest Westminster party, to add to its status as such in the Assembly and local government. The party is polling just below its 2019 performance. That election saw Sinn Féin gain a notable scalp, John Finucane ousting the DUP’s Deputy Leader, Nigel Dodds in North Belfast, but the party’s performance was poor overall, almost seven percentage points down compared to 2017.

Sinn Féin was blamed for collapsing Stormont in 2017 and its nationalist rival, the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) reversed its decline evident since the Good Friday Agreement (much of which it wrote) to make two gains. One of those captures was from Sinn Féin, SDLP leader Colum Eastwood triumphing in Foyle by a stunning 17,000 votes.

Regaining the seat looks difficult for Sinn Féin. For republicans, it’s more a case of borrowing an ancient unionist slogan of ‘what we have, we hold’. Retaining its seven seats could be enough to make Sinn Féin the largest party if the DUP does hit trouble.

Sinn Féin has made progress at most elections in both jurisdictions on the island of Ireland since the Good Friday Agreement. Yet the 2019 drop in Westminster vote share was matched by big problems in that year’s local and European contests south of the border. The party lost half of its council seats. Party President Mary Lou McDonald presided over another underwhelming set of performances in the same contests this month. Sinn Fein’s 12% first preference vote share was 20 percentage points below the party’s opinion poll rating one year earlier.

Yet in the North, Sinn Féin has not been afflicted by the issue of immigration which has eroded some of its working-class vote down South. Most Northern nationalists have only two parties from which to choose – and Sinn Féin dominates.

This owes much to how modern Sinn Féin has changed from its conflict incarnation. Its leader in the north, First Minister, Michelle O’Neill, insists she is a ‘First Minister for all’. That has involved appearances at the late Queen’s funeral and the King’s coronation. Swearing an oath of allegiance to a British Monarch is another matter however and the party is unlikely to change its policy of abstention from Westminster.

Sinn Féin is also staying away from South Belfast for this contest. ‘Election pact’ is the term that dare not speak its name, amid tortuous denials of the label, but the move will undoubtedly assist the SDLP’s Claire Hanna, who looks certain to be re-elected.

Little in policy terms separates the SDLP from contemporary Sinn Féin, apart from Westminster abstention. Sinn Féin holds the obvious structural advantage of being an all-Ireland party. Believing in a united Ireland but only standing in one corner and unable to tie-up any permanent arrangement with a party south of the border does not assist the SDLP. The party has insufficient Stormont seats for a place in the Northern Ireland Executive, although fronting the official Opposition may do no harm.

Sinn Féin leads Eastwood’s party (he is largely blameless) in all age categories under-65, as those politically socialised in an era of SDLP dominance enter old age. Westminster elections represent a good opportunity for the SDLP to bite back, however, on the representation versus abstention faultline.

Beyond Unionism and Nationalism: can Alliance maintain progress?

The election is also a difficult test for the party that straddles Northern Ireland’s divide, Alliance. It has made great strides in recent years. The ‘Alliance surge’ saw the party average 16% of the vote in 2019, more than double its average share since foundation in 1970. Alliance more than doubled its Assembly representation to 17 in 2022 and made further gains in local elections in 2023.

The general election will see if those contests were perfect, but passing, storms benefitting Alliance. The context was beneficial: Brexit, collapsed political institutions and a willingness of voters to transfer to the centre but not across the divide, saw the party soar. Alliance was the only major party to contest every seat last time and does likewise in 2024.

Alliance’s rise should have surprised less than it has. Since 2006, those saying they are ‘neither unionist nor nationalist’, the party’s natural reservoir, have been the largest category of elector. In that respect, Northern Ireland has thawed. Yet many ‘neithers’ don’t vote, whereas most unionists and nationalists do. That’s why more than 80% of votes in the region’s elections are for unionist or nationalist parties.

Alliance wants to change the rules of the game. Institutional reform is a key plank of its platform. That means no longer enshrining the unionist versus nationalist divide, scrapping such designations in the Assembly and introducing weighted majority voting to replace sectarian counting. The party wants to end the system whereby if the First or deputy First Minister, who must be from the rival blocs, quit the Executive, Northern Ireland’s government falls. That’s what happened when Sinn Féin’s Martin McGuinness quit in 2017 and again when the DUP’s Paul Givan walked out in 2022.

Stormont has been down for nearly 70% of the time since 2017 and for 40% of the post-Good Friday Agreement era. This has contributed to the worst crisis in the NHS anywhere in the UK (1 in 4 adults on a waiting list); absence of a coherent programme for government and chronic dependence upon the UK Treasury.

Possible consequences: party leadership; border poll?

The election has two possible sets of consequences. One concerns party leaderships. The political futures of Gavin Robinson, Colum Eastwood and even Naomi Long may be at stake. Should he lose, Robinson could be co-opted into Stormont and remain DUP leader but it would be messy and unedifying. The optics would be desperate and undemocratic, even by the standards of an Assembly where almost one-third of its intake (29 of 90) were co-opted for the 2017-22 session. Eastwood knows he must hold his seat for his own and his party’s sake; an SDLP with Westminster representation in both of Northern Ireland’s two major cities remains credible. Long has raised Alliance’s game but that creates the problem of increased expectations.

The second, much longer-term possible consequence, is that the election might indicate whether a referendum, aka a border poll, on Northern Ireland’s constitutional future is any nearer. Sinn Féin wants one within a decade. The Secretary of State for Northern Ireland decides. The only criterion is that one must be called when it appears to the minister that there is a majority in favour of change.

On evidence to date, there is more chance of obtaining a date for the Second Coming than for a border poll from Hilary Benn, Shadow Secretary for the last nine months of the most recent parliament, and Keir Starmer is similarly dismissive.

Although legal efforts to create fixed criteria have floundered, a combination of Sinn Féin as largest party, an overall rise in the nationalist vote and a net decline in support for unionist parties will increase pressure for a referendum. It’s not as if the end of the Union is nigh though. Averaging across post-Brexit opinion polls, support for Northern Ireland remaining in the UK averages 49% - hardly a resounding endorsement but it has stabilised after a sharp drop immediately after the 2016 EU withdrawal vote. Support for a united Ireland is on 35% and needs a big boost to get a referendum called.

The ‘don’t knows’ need to break overwhelmingly for Irish unity. More Alliance Party members favour unity than Union but with lots of undecideds. It would need their voters to break decisively for unity to win a referendum. Demographic change favours those backing a united Ireland as Catholics now outnumber Protestants – but Protestants are more united in backing the Union than are Catholics in wanting a United Ireland.

So, there is much to play for at this election, even if Northern Ireland is at the margins not the centre. 136 candidates (up 33% from last time) chase a mere 18 seats. As sideshows go, it’s rather interesting and important. Here are (probably) the seven biggest battlegrounds:

East Belfast

The most interesting contest of all. It’s the regular head-to-head between the DUP and Alliance leaders, Gavin Robinson and Naomi Long but with some differences. Robinson leads 3-0 but has only 1,819 votes spare. Some of those may disappear to the TUV, whose last foray into this parliamentary seat contributed to Long’s 2010 victory over the then DUP leader Peter Robinson. Unlike 2019 however, the Greens and SDLP stand this time and may take a few votes from Alliance. Long is currently very slight favourite but it’s not one for big wagers.

North Belfast

The bitterest battle of 2019. Sinn Fein’s John Finucane, whose father was murdered by loyalist paramilitaries, captured the seat from the DUP’s Nigel (now Lord) Dodds. Finucane’s majority was under 2,000. This time the SDLP is standing, peeling away a few nationalist votes but the effect of that is neutered by the TUV’s decision to also contest the seat, which may chip away at the DUP vote. It looks a probable, but not certain, Sinn Féin hold.

Fermanagh and South Tyrone

The UK’s most marginal constituency. The average majority this century has been a mere 366 votes and the most recent 57. We’ve been down to 4 votes (2010). Sinn Féin has held the seat since 2001, apart from the UUP’s tenure from 2015-17. Pat Cullen, of Royal College of Nursing fame, stands for Sinn Féin. Another close battle with the UUP seems assured, with the other unionist parties standing aside.

South Antrim

The only real DUP versus UUP contest and the only seat where the latter starts favourite. Former Health Minister Robin Swann is high profile locally and stands a reasonable chance of ousting the DUP’s Paul Girvan, who took the seat from the UUP in 2017. Only 2,689 separated the parties last time.

Lagan Valley

The circumstances of Jeffrey Donaldson’s departure from politics make this constituency more uncertain. Donaldson had held the seat since 1997, initially for the UUP, then the DUP since 2005. His majority was slashed from 19,000 to 6,500 in the 2019 Alliance surge and Sorcha Eastwood hopes to take the seat for Alliance this time. Assembly member Jonathan Buckley stands for the DUP and should hold on in a predominantly unionist constituency but it’s not a certainty.

Foyle

It is crucial for the SDLP and its leader that this seat is held. Always an SDLP stronghold since creation in 1983, this was lost to Sinn Féin in 2017 but recaptured by SDLP leader Colum Eastwood in 2019. Remarkably, Eastwood polled a higher vote than John Hume, the closest thing to a local saint, ever managed and a majority of 17,000 ought to be a big enough cushion.

North Down

Alliance’s only seat, captured by Deputy Leader Stephen Farry in 2019. Farry bids to be the first Alliance MP to retain their berth but faces stiff competition from Independent Unionist, Alex Easton. Despite quitting the DUP 3 years ago, Easton is backed by the party, another oddity among many in Northern Irish politics. Easton hopes that the unionist vote weighs heavily behind him rather than peeling off to the UUP candidate, Colonel Tim Collins, whose eve-of-battle speech in Iraq was displayed in the White House during the Bush Presidency. Collins has, however, made some gaffes, most recently when he complained how it was cheaper to service his Rolls-Royce back home in England than a Ford Fiesta in Northern Ireland. That raised eyebrows even in the region’s most affluent constituency.

Seat Previews: Somerset

(Seats in the Bristol area coming later in the week…)

Bridgwater

Current Holder: Conservative

Majority: 16,724, 37%

Prediction: Lean Conservative

The boundary commission have really carved up Somerset. Lots of changes. This is two thirds of the old constituency and a chunk of Wells which has probably helped the Conservatives by creating a split opposition vote. The veteran MP Ian Liddell-Grainger has shifted over to the safer Tiverton and Minehead, so the Conservative candidate is Ashley Fox who was a senior MEP for the party, and was chief whip for the group of MEPs that the Tories used to be part of. Some MRPs have this going Labour and their candidate is Leigh Redman, a councillor and business manager.

Frome and East Somerset

Current Holder: Conservative

Majority: 12,395, 26%

Prediction: Lean Conservative

Same story again in this new constituency, roughly equally split between the old Somerton and Frome and North East Somerset seats. A split opposition vote might allow the Tories to hold on, in what is effect a three way marginal. It’s further complicated by the fact that the Lib Dems won Somerton and Frome in a by-election last year when David Warburton resigned. But the winner of that, Sarah Dyke, is standing in the next door constituency. All of which means both the Survation and YouGov MRPs have all three parties within five points of each other. It’s a battle of the local candidates. The Conservative is Lucy Trimnell, who served in the navy and then went on to be a maths teacher and councillor. Labour have Robin Moss, a councillor who runs a youth centre. And the Lib Dem have Anna Sabine, a local businesswoman. This one could go anywhere.

Glastonbury and Somerton

Current Holder: Conservative

Majority: 14,183, 26.5%

Prediction: Lean LD

This is the rest of Somerton and Frome with bits of Wells and Yeovil added in. Though the Tory majority is similar to the previous seat this one is different in two ways. First the Lib Dems are clear second place on the notionals, and secondly the MP, Sarah Dyke, who won the Somerton and Frome by-election is standing here, making the Lib Dems the incumbents. Dyke is a local who owns a second hand shop. The Conservative candidate is Faye Purbrick, who stood and lost in the by-election, she’s a local councillor and business consultant.

Taunton and Wellington

Current Holder: Conservative

Majority: 8,536, 15.5%

Prediction: Lean LD

This is most of the old Taunton Deane constituency but slightly smaller, which reduces the Conservative majority and makes this a strong target for the Lib Dems in a seat they held till 2015. The incumbent MP is Rebecca Pow, who spent most of her career as a specialist agriculture journalist before entering Parliament. She’s held a number of junior roles and is currently in Defra. Her Lib Dem opponent is Gideon Amos an architect currently working on renewable energy projects.

Tiverton and Minehead

Current Holder: Conservative

Majority: 20,665, 42%

Prediction: Likely Conservative

Another new seat built out of the remaining third of Tiverton and Honiton, a third of Bridgwater and some of Taunton Deane. One of the safer Tory seats, and again a split opposition which should help them hold it. The MP is Iain Liddell-Grainger, whose been a right-wing backbencher willing to cause trouble since 2001. He’s of aristocratic stock and a great-great-great grandson of Queen Victoria. Likely to still be there as part of the diminished Tory party.

Wells and Mendip Hills

Current Holder: Conservative

Majority: 14,295, 25.5%

Prediction: Lean LD

This is half of the old Wells seat plus a bunch of wards from three other constituencies. It’s another Tory vs LD battle and the Libs might have the edge in part because their candidate is the former MP for Wells Tessa Munt. She lost the seat to James Heappey in 2015 but he’s now standing down. The new constituency is more Tory giving their new candidate, Meg Powell-Chandler, a chance of holding on. A serial media SPAD whose worked across four different departments, her biggest role was three years in Boris Johnson’s media team. If she wins she’ll be one the better connected new Tories. But I think Munt might sneak it.

Yeovil

Current Holder: Conservatives

Majority: 14,638, 27%

Prediction: Lean LD

A largely unchanged, if slightly smaller, seat. This is a real tossup between the Lib Dems and Tories. It was a Lib Dem fortress for a long time. Won by Paddy Ashdown in 1983 (as a Liberal), handed on to David Laws, and not lost until 2015. But Tory Marcus Fysh has built up a decent majority since then, giving him a chance of holding on. A right-wing, social conservative, Truss-backer, he’s only briefly held ministerial position when she was PM. The Lib Dem candidate is Adam Dance, a long time councillor and owner of a landscaping business.

Running Total

Labour: 45 (+35)

Conservative: 43 (-61)

Liberal Democrat: 27 (+26)

Green 1

The Alliance certainly seem to be getting lots of volunteers out campaigning, if social media is indicative at least. Often a younger age profile too than one sees elsewhere.

Also, it’s not just that the Labour Party doesn’t field candidates in Northern Ireland. You literally cannot join it.