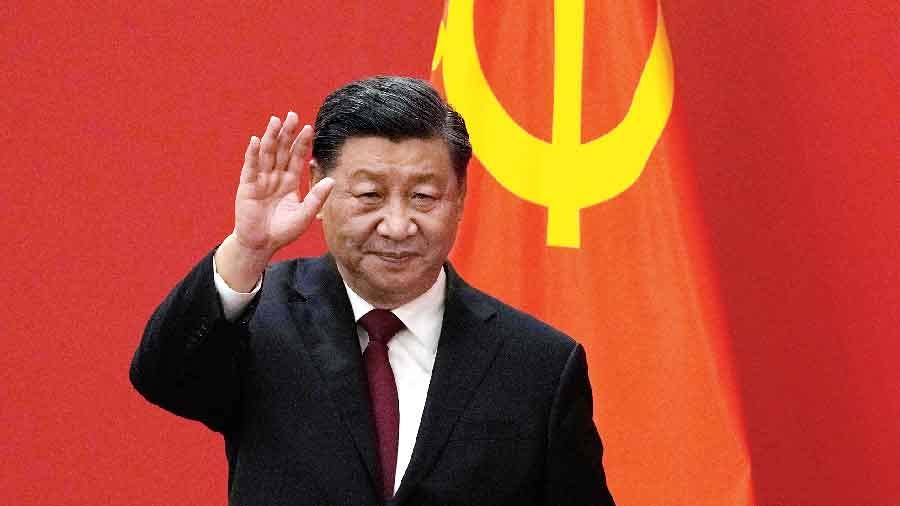

The G20 meeting in Bali in November 2022 was a showcase for China’s return to international diplomacy at the highest level. Xi Jinping is now firmly back on the international circuit, and China continues to portray itself as a power rising to global influence, with plenty of evidence, from cyberspace to outer space, to back up its claim. Yet the domestic situation is weaker than the CCP (Chinese Communist Party) would have hoped a year ago, with a chaotic winding down of the zero-covid policy, new American laws to deny China high-technology exports, and a shaky financial and property sector. Beijing has also raised the tone of its rhetoric on the unification of Taiwan with the mainland. But this move, if it ever came about, would be more likely to exacerbate China’s problems for years, if not decades, rather than solve them. Bali marks Chinese re-entry into the world, while revealing the uncertainties that could undermine it.

China did make the most of its G20 presence. Unmasked and confident, Xi Jinping held court, giving or withholding favour from leaders eager to be seen with him. There was little doubt that he would meet Joe Biden, but other leaders seemed to compete for invitations. Emmanuel Macron and Anthony Albanese were invited in, with the latter’s visit seen as a sign of thaw in the icy relationship between Canberra and Beijing. Others, including the UK’s Rishi Sunak, were not given a meeting, though it’s unclear whether the planned bilateral with Sunak fell victim to the erroneous report that Russia had bombed Poland, or Chinese anger at Sunak suggesting support for Taiwan.

Yet the demonstration of power by Xi belied the hesitancy that seems afoot in Beijing about China’s international strategy. The years of the pandemic saw not only US-China relations entering a period of deep freeze, but also a general lowering of favourability for China in the Global North, in particular in the Anglophone countries. The Global South remained overall friendlier, but it was hard to avoid the impression that it was Chinese Belt and Road funding, not values, that kept them enthusiastic. And all this was before the dramatic turn in covid policy that followed mass protests in China in early December. China’s domestic woes, notably a weak economy, are not terminal but they are undoubtedly serious. And solving them is dependent on a clearer sense of where China’s international relations are going.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Comment is Freed to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.