This month’s guest poster is John Kingman, Chair of Legal and General, Britain’s largest investor and Barclay’s UK retail bank.

Previously John spent much of his career at the Treasury. Under Gordon Brown he was responsible for growth policy, and played a critical role in the UK’s response to the financial crisis, negotiating deals with nationalised banks and then becoming the first CEO of UK Financial Investments which managed the government’s stakes. He returned in 2012 to become Second Permanent Secretary, again with a focus on growth policy, leaving in 2016. He then spent five years as the first Chair of UK Research & Innovation, which oversees Government science funding.

I met John while researching my book and those who’ve read it will have seen some of his thoughtful contributions. In this post he looks at some of the things the government should do if they’re serious about economic growth being their main priority.

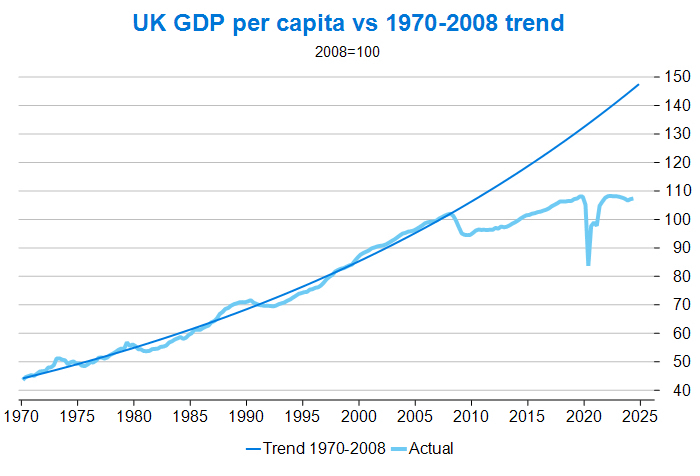

Britain’s economy is in a long deep funk. Since the 2008 crisis, GDP per head has crawled at less than 0.5% a year; had the economy instead grown at its previous long-run trend, it would now be around 40% larger.

This fact determines everything in Britain – higher growth would have meant very different living standards, but much better public services too.

Britain’s new Government clearly gets this: it has claimed higher growth as its central governing purpose.

However, the recent Budget has shown how tricky the terrain is. The Budget made sensible tweaks to the fiscal framework to unlock some additional public investment. The markets’ jittery reaction to even these fairly modest steps showed how, through no fault of hers, the Chancellor is having to operate awkwardly close to the edge of investors’ appetite.

Next year she will ask investors to lend her £300bn, and not much less in each of the following two years. There are few natural buyers of gilts. So she has very little fiscal room for manoeuvre.

She also has many mouths to feed – including excellent causes which unfortunately have little to do with growth. The great bulk of the additional capital is going to hospitals, schools, defence and carbon capture – all extremely deserving, no doubt, but sadly none of these is going to do much if anything for productivity or the long-term growth rate.

To make way for all this, starkly, the transport capital budget – where the link to growth is clearest – is actually being cut. Critical projects like the Transpennine upgrade, intended to capture what should be natural agglomeration benefits between Britain’s second and fourth cities, just 40 miles apart, appear dangerously close to the long grass (“maintain momentum … by progressing planning and design works to support future delivery” is the Budget Yes Minister-speak).

Meanwhile there has been little if any change in international investors’ excessively downbeat perception of Britain. Investors have become used to seeing the UK as a persistently low-growth economy prone to sporadic acts of violent self-harm. If the new Government could shift this - as should be eminently possible - one could even imagine a very big prize, to get into a virtuous cycle in which improved investor sentiment itself drove more private investment, and the prospect of higher growth thus started to become self-reinforcing.

This higher growth would also give the Chancellor a way out – the only way out – of the tight fiscal box in which the last Government imprisoned her.

Again the Government clearly understands this. Unfortunately, the evidence of financial markets is that there is no sign of it happening – yet.

What this all underlines is the colossal nature of the task, if we are really to yank the economy onto a fundamentally different trajectory. If the Government is to achieve anything like what it says it wants to achieve, it is going to have to think bigger and bolder and on a wider front.

In terms of scale of the challenge, the only really relevant comparison in living UK memory - however different the circumstances and political context - was that facing the Thatcher government in 1979.

Some ideas

That is easy to say. The trickier part is: what, specifically, could the Government actually do?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Comment is Freed to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.