Three seconds

TikTok and the future of politics

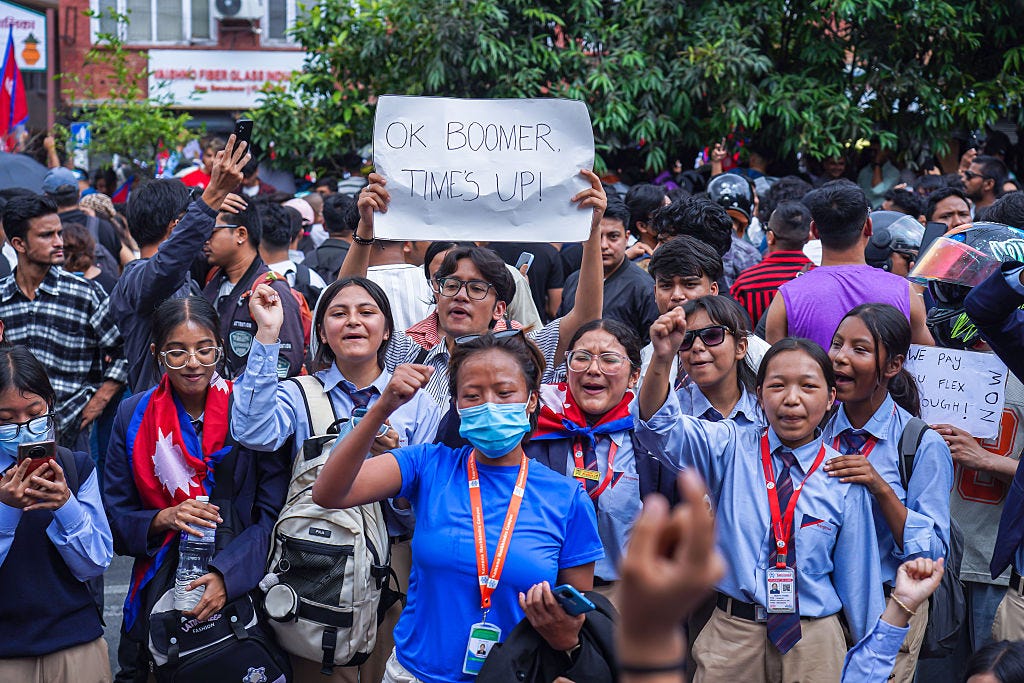

Gen Z protesters in Nepal who brought down the government earlier this month (Photo by Ambir Tolang/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

I suspect many readers knew little, if anything, about Charlie Kirk before his murder on the 10th September. But if you have teenage kids they probably did. For months my son has been being showing me clips on TikTok of Kirk being “owned” by progressive students during his tour of university campuses. In schools across the UK this has been the biggest story of the year by far. With his fast-speaking and combative style, Kirk was perfectly suited to a site where you have an average of three seconds to engage the viewer before they flick on to the next video.

Meanwhile, my eldest daughter has been captivated by the overthrow of the Nepalese Prime Minister, K. P. Sharma Oli, and his replacement by former Supreme Court Justice Sushila Karki. Not only did she know about this through watching TikTok videos but the revolution itself was driven on the streaming site by young people barely older than her.

The immediate trigger for protests was the government’s decision to shut down dozens of social media sites including Facebook, X and YouTube. Ministers claimed this was because the sites were failing to abide by new regulations. But the “Gen Z” protestors believed the real reason was to stop the spread of viral memes about nepotism, with videos of politicians’ children living in luxury at the heart of the campaign. Protests quickly descended into violence and the resignation of ministers. Incredibly, the new Prime Minister was chosen via a vote on Discord (another social media platform).

Though Nepal is one of the most dramatic examples of this type of “Gen Z” protest it is not unique. Last year the Bangladeshi government was overthrown by a similar demographic, and there were mass protests in Nairobi at new taxes organised over TikTok and other platforms. In August, the Indonesian government found themselves facing violent protests over salary boosts for politicians. Tellingly, one of their countermeasures was to ask TikTok to stop live streaming. The average age in all of these countries is 30 or below (25 in Nepal and just 20 in Kenya), compared to 41 in the UK. That magnifies the effect both of disenchantment with lack of employment opportunities but also the power of new forms of politics.

While all this has been going on the US and China have been negotiating a deal over TikTok’s future in America. That a video streaming website would be at the heart of a complex trade deal with global consequences is an indication of how important it has become. Trump has been personally involved, discussing the issue with Xi Jinping, because he knows how critical the site is for boosting his support. TikTok users who get their news from the site were one of the groups with the biggest swing from Biden to him in last year’s election.

In the UK, TikTok is already the biggest source of news for 12-15 year olds and rising up the rankings fast for older teenagers and those in their 20s and 30s. Amongst all adults it’s now as big a news source as ITV, Channel 4 and the Daily Mail. It’s by far the fastest growing social media platform globally, with over a billion monthly users. Critically users spend far more time on the site than others.

So why has it been so successful? What are the risks, both geopolitically and in terms of domestic politics? How is it going to change political engagement? And can a generation of politicians brought up on older forms of media make it work for them?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Comment is Freed to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.