The Policy Paradox

The more obvious an idea is the less likely it will happen.

The longer you work in policy the more you realise new ideas are extremely rare. Even ideas that seem new are usually old ones repackaged and given a different spin. It’s why so many people who’ve been around politics for a long time develop an air of weary cynicism. When you’ve heard the same idea in a hundred different panel sessions, with a glass of cheap white wine warming in your hand, it’s hard to get excited.

I’ve been around for a while now and have occasionally found myself drifting into the cynicial “it’s been tried before” mode. So I’m trying to avoid it by taking a different approach. When I’m talking to a young think-tanker or political aide, whose enthusiam is not yet dimmed, I try not to dismiss ideas that have been doing the rounds for a while, but ask a different question: “given you’re not the first person to think of this why hasn’t it happened before?”

Just because something hasn’t worked, or has been blocked, in the past, it doesn’t mean it can’t work now. But it is important to understand the history and explain why it can be different this time.

The more of these discussions I have the more I have come to realise that there’s an odd paradox that applies to every policy area: the more obvious the idea, the less likely it is to happen. I don’t just mean obvious to me. There are plenty of policies that I personally – as a member of the dissolute liberal new elite – think are no brainers that are nevertheless hotly contested. No, these are ideas that everyone, bar perhaps a tiny ideological fringe, agree with, and that, at any of those panel events, will get a room full of appreciative nods, but nevertheless don’t happen.

This struck me with renewed force when reading a recent review of the health system by Patricia Hewitt, the former New Labour health minister. Hewitt argues for a greater focus on preventative health. More money should be spent reducing the risks of illness in the first place. This would save the NHS time and money, while enabling people to lead healthier and happier lives.

As far as I’m aware absolutely no one disagrees with this. Some dispute the idea that it will save much money, as healthier people live longer and ultimately may require more healthcare over their lives, but no one disagrees with the basic principle that it’s better to prevent illness than manage its consequences.

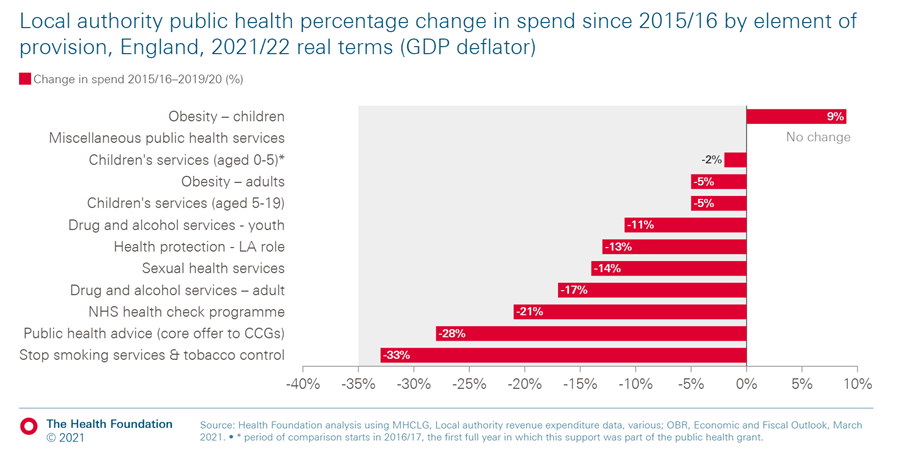

This includes the government. The report was commissioned, and welcomed by, the Chancellor Jeremy Hunt. When he was health secretary his “long term plan” emphasised prevention. Every health and shadow health secretary pays lip service to the idea. There have been hundreds of reports over the years making the unarguable case. And yet since 2015/16 the public health grant to local authorities – the main budget for preventative health - has fallen by 24% in real terms, even as overall healthcare spending has continued to rise. As a result spending in every key area of preventative health, except childhood obesity, has fallen.

So despite everyone agreeing with the policy – including the person who was health secretary in 2015 and is Chancellor now – funding has been cut rather than increased. Hewitt, being an experienced policymaker, explicitly asks the “why will it be different this time” question in her report but her answers are unconvincing because she doesn’t acknowledge the fundmental reason why it keeps happening.

What explains the paradox? Why are the most widely supported things the least likely to happen? The simple answer is that if an idea is that obvious and not ideologically contested, and has featured over many years in reports and speeches, and still hasn’t happened, then the reason it’s not happening has nothing to do with support for the principle. Something else is acting as a barrier. More advocacy for the policy will not change this. As I tell the eager young think-tankers I meet, there’s no point writing another report making the case. The blockage needs to be identified and removed.

In my experience there are three core categories of barrier that prevent the obvious ideas happening: spending rules; misdiagnosis; and fear of the electorate.

Spending rules

The failure to make any progress on preventative health falls squarely into the first category. It doesn’t happen because our processes for deciding what to spend money on are staggeringly unstrategic. The Treasury’s objective in a spending review is to hit a target number that is driven by an arbitrary fiscal rule. To do this they have to overcome various obstacles including promises to protect highly politically sensitive budgets like hospitals and schools. One trick to achieve this is to move money into unprotected budgets. They did this with public health during the coalition years, removing the money from the NHS and giving it to local authorities instead.

Once it was in was in the local government budget it could be cut while keeping promises to protect NHS spending. The same trick was applied to post-16 spending in education which falls outside the government’s definition of schools (something that would no doubt surprise many parents and students). Despite endless speeches from politicians about the importance of further education and vocational courses, it has been cut by around 20%. This is because it can be while keeping promises to protect school budgets.

I quoted a former very senior Treasury civil servant in an earlier post on the NHS:

“In successive Spending Reviews and Budgets NHS England and the Department of Health have pressed for the maximum headline increase they can and the Treasury has sought to offset the increases by squeezing the separate more vulnerable budgets. While everyone can see that is a mistake, they can't find a way out.”

This fundamental flaw in the way we make spending decisions is a key reason for the policy paradox. If the government’s entire strategic approach is being driven by a rigid spending limit then it will inevitably push money towards short-term priorities. Rehabilitation will get less focus than prisons which will get less focus than policing. Net zero will remain a long-term goal with limited upfront investment. And so on. There is no value in more speeches and reports arguing for these things without tackling this problem – government will accept the analysis, they just won’t do anything about it.

Campaigners have tried to find workarounds to this – most commonly pushing for targets to be enshrined in law to force governments to prioritise them. But this hasn’t worked either as the laws always allow for opt-outs as we’ve seen with child poverty and international aid. Ultimately whatever fiscal rule the Treasury is following at the time will always reassert itself as the primary basis for decision making, outside of a major crisis like the bank collapse or the pandemic. There are a lot of obvious policies that will never happen, or never be sustained, until we move to a more sophisticated approach to spending control.

Misdiagnosis

The second category covers policy statements that are agreed on by nearly everyone at a high level but involve a misdiagnosis of the problem at hand, leading to politicians pulling at levers that aren’t connected to anything.

Vocational education is a classic example. One of the most reliable applause lines at an education event is to say something like: “we must end the stigma against vocational qualifications and create parity of esteem with academic routes”. You will struggle to find anyone who disagrees with the principle of valuing vocational courses more highly. Unfortunately, politicians and policymakers have been saying the same thing for around 170 years – Prince Albert set up a Royal Commission in 1851 that fretted about our lack of focus on industrial skills. You would have thought that they might have figured out by now that esteem is not in their gift to give.

The misdiagnosis here is the belief that academic qualifications are more valued either for reasons of cultural snobbery, or because vocational qualifications are poor quality. But it is simply a function of labour markets. The vast majority of the best paid jobs are only available to graduates and, in practice, to graduates of the most prestigious universities. The best way to get on to those courses is by doing A-levels. It is therefore entirely rational to esteem academic qualifications more highly. And there is no country in the world where this isn’t true. Germany is usually wheeled out as an example of an alternative, successful approach but it has exactly the same problem, with huge shortages in manufacturing roles as vocational courses are left unfilled. The graduate premium applies there as it does everywhere else.

The belief that “esteem” is something that governments can provide means politicians keep pulling at the wrong policy levers. We are currently in the midst of yet another attempt to develop a new suite of vocational qualifications that will match the prestige of A-levels – this time called T-levels. This has been tried multiple times before – NVQS, ACVES, Diplomas etc etc. And they always run into the same problem. By definition the group of young people who are willing to take the new qualifications are those who have not got a swathe of strong GCSE results. If the qualification is really as difficult as an A-level they will mostly fail. If it’s easier then it won’t have the same level of prestige.

Exactly the same thing is happening with T-levels. Thus the requirement to have GCSE level maths and English by the end of the course has been dropped for fear it would lead to an extremely high failure rate. As this suggests, repeatedly fiddling around with the qualifications makes the problem worse as it destabilises the system and leads to those existing certificates, like BTECs, that are at least understood by employers being scrapped.

Another example – found in many policy areas – is the assertion that targets are bad because they lead to gaming. This is true. I’ve said it myself, and it will, again, guarantee a room full of nods. Here the misdiagnosis is that removing or downgrading targets will make things better. Nope. The reason some people or institutions are gaming the target is they aren’t capable of meeting it. Removing the target just means you no longer know they are incapable of meeting it. In the meantime the people who were genuinely meeting the target are now under less pressure to do so. Performance overall will drop.

The 4 hour A&E waiting time target is a good example. New Labour put huge emphasis (and resource) into ensuring almost no one had to wait longer than this. It was heavily criticised for leading to gaming – for instance patients being unnecessarily admitted after 3 hours and 59 minutes. And there was undoubtedly some gaming. But it also worked. An IFS study found a 14% reduction in mortality while satisfaction with the NHS hit record levels.

The target was never removed but it was downgraded under the Coalition and Conservative governments. It’s hard to untangle the impact of that from lower increases in funding than Labour offered but waiting times were rising well before the pandemic hit, and there is now much wider variation between hospital trusts. The target has recently been upgraded again albeit at a much lower level. Labour have promised to bring the old target back. The Welsh and Scottish governments have been through a similar process of discovery when it comes to attainment targets for schools.

Fear of the electorate

There are plenty of policies that are regularly advocated by think-tanks and experts that are not pursued because they would be unpopular, at least with key voter demographics. But in most cases politicians who don’t want to pursue them will be happy to argue publicly against them. For instance most experts on drug use would argue criminalising laughing gas was a bad idea but a majority of the British public support doing so, and so will Tory and Labour spokespeople on the grounds they are dangerous and are connected to anti-social behaviour.

There is a subset of policies, though, that there is no plausible argument against but still don’t happen because, it is assumed, voters wouldn’t like them. Politicians don’t actively argue against them but just stay quiet. An obvious example is council tax revaluation. Council tax is badly designed for all sorts of reasons: the bands are too wide and the difference between them too small, so it’s extremely regressive. But the bit that no can defend is that, in England, properties have never been revalued since the tax was introduced in 1991. Over the last 32 years house prices in some parts of the country have gone up much higher than others. The IFS estimate they are six times higher in London than in 1995 but only three times higher in the North-East. This goes directly against the stated desire of both main parties to level up parts of the country that have seen less economic growth in recent decades.

I’ve never seen any politician try to defend the status quo. On the rare occasion they’re asked about it they’ll mumble something about it being complex and how it needs careful consideration or some such. Depending on how it was done it could raise some much needed money. Yet there seems no prospect of it happening for the obvious reason that many homeowners in London and the South-East would find themselves in higher bands.

With these types of policies there is little point putting out another report bemoaning the failure to revalue council tax unless you have a proposal for dealing with the politics.

Why will it be different this time?

I’m sure they are types and categories I’ve missed of obvious policies that never happen (suggestions in the comments!) but hopefully I’ve done enough to persuade readers that “why will it be different this time?” is a question worth asking more often.

It's taken me a long time to realise it but ideas are overrated in policy. The real skill is figuring out how to make the ideas we already have happen. Finding ways round the structural barriers to good policy; correcting misperceptions about the causes of widely accepted problems; devising cunning ways to make unpopular but necessary policies palatable. It sounds less exciting than coming up with a big new idea, but it’s a lot more useful.

And yet things can be done if you have the right momentum from both ministers and civil service. Back when I was at The Guardian, in 2006 I launched a campaign called "Free Our Data", which advocated making non-personal data held by government free for commercial or personal reuse. (The "non-personal" part is VERY important, obvs.) An example would be map data from Ordnance Survey, which is run as a little company inside government - a "trading fund".

We slogged along for years without much to show for it, until the Brown government in 2010, when Tom Watson became Cabinet Office minister, and was completely in tune with what we wanted to do. There were also some civil servants who thought it was a good idea.

Tom really pushed things through: OS objected strenuously, but he recruited other ministers to the cause and got momentum for this change to happen. Bear in mind that it would blow a hole in OS's budget, so would require Treasury to approve it (or at least not disapprove it). It did help too that Tim Berners-Lee told Gordon Brown at a dinner that this was a good idea and should go ahead.

There were studies and costings and examinations and so on, but in the end it was about pulling the trigger. And just before the 2010 election, the Brown government did, as part of a bigger opening up of data. It helped that the Tories were also looking at the idea, so there was a competitive element.

Some of that was about the timing: in 2010 the whole "internet everywhere" was taking off through mobile, which meant apps, which meant location and and also companies setting up to take advantage of the growing appetite for smartphones and apps.

But the remarkable thing is that it might have been a policy which had never been tried before, so your question of "why didn't this work the last time?" never arose. The one question that did stump me when I first talked about FOD in public was when Tom Steinberg of MySociety, who had civil service experience, said "How can I make the financial case for making this data free to Treasury?"

Only later - jeu d'escalier - did I think of the GPS system, where the US government funds the satellites that then provide navigation for cars and people; the former saves far more in time/ delays/etc than it costs. Finding those sorts of multipliers is tricky when you're first doing policy.

Thanks for indulging me. But I think there is a lesson: a good policy finds its time, and its champion, so perhaps it's worth trying again just because "this time it's right". FOD could never have worked before the internet, before widespread availability of mobiles.

The one part where we failed was getting postcodes included as part of the free data. Apparently that was down to Vince Cable at some point post-2010. Arse.

Really good. One of the big obvious policy solutions to sewage in the rivers is retrofit sustainable drainage systems. Hasn't happened because it needs to be delivered jointly by local government and water companies. This government just seems to hate local government and be obsessed with starving them of funds. Setting local government free, funding it, and setting some regulations around this, would go a long way to starting to tackle this issue.