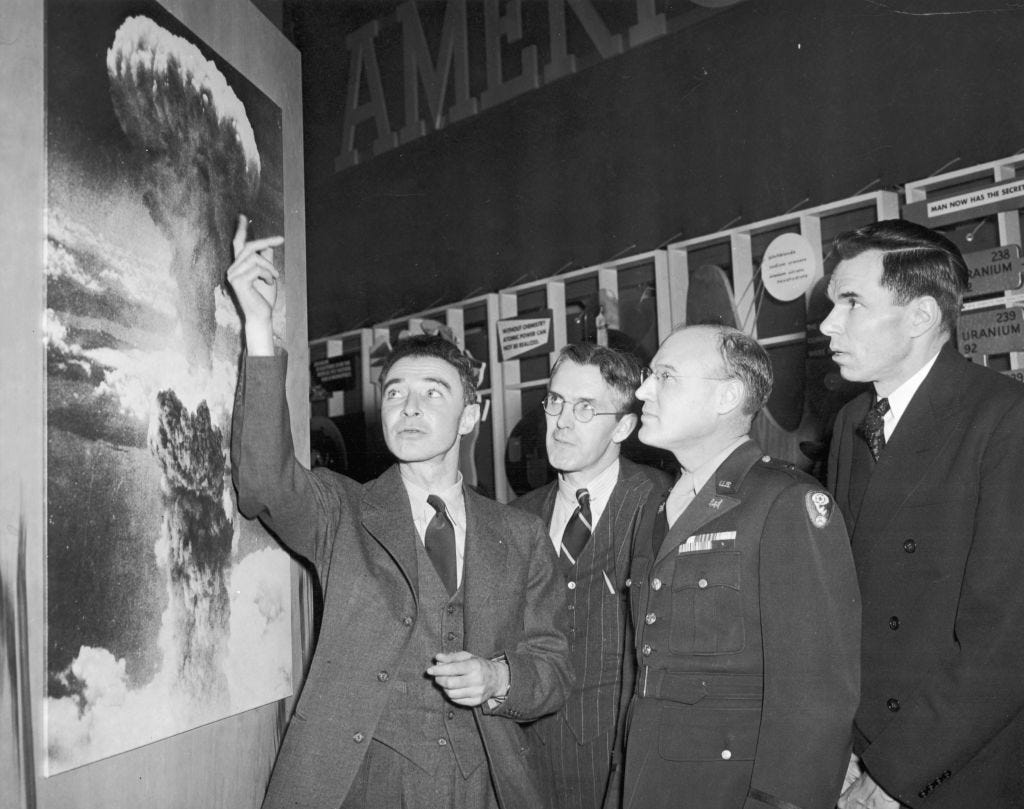

Robert Oppenheimer discusses the mushroom cloud over Nagasaki

‘We may anticipate a state of affairs in which two Great Powers will each be in a position to put an end to the civilization and life of the other, though not without risking its own. We may be likened to two scorpions in a bottle, each capable of killing the other, but only at the risk of his own life.’

Robert Oppenheimer, ‘Atomic Weapons and American Policy,’ Foreign Affairs, July 1953,

I enjoyed Oppenheimer. Normally when I watch films with historical themes about which I know something I grumble away because of obvious errors or a wholly distorted narrative. In this case Christopher Nolan has done better than most in putting together a complex story in a way that most historians would consider reasonably authentic. He has used as his bible American Prometheus, the well-regarded biography of Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and the late Martin Sherwin. (Bird gave the film a ringing endorsement).

Even when he has not been able to spend time on important aspects of the story Nolan has at least alluded to them. As familiar characters made fleeting appearances – Leo Szilard, Enrico Fermi, Vannevar Bush – my knowledge of their back stories helped me enjoy the film more. I suspect for others it would have been harder to keep track of the long cast of nerdy scientists. The chap playing the bongo drums in the intense glow of the Trinity test, by the way, was the great Richard Feynman.

Errors and Omissions

But there are still issues. Inevitably in any American war story, the British contribution is downplayed. In this case the main role of the British contingent at Los Alamos is to insert a Soviet spy – Klaus Fuchs - into the Manhattan project. Yet not only did other British scientists make important contributions to the project, without the original British work on the feasibility of a fission weapon there might well not have been any project at all. Nolan puts his emphasis on the letter to the President drafted by Leo Szilard and signed by Albert Einstein in September 1939. This gave the US programme a push but it remain lacklustre until it got an impetus from the UK’s MAUD report, which showed a way forward, when it was passed on to Roosevelt’s scientific advisors during the summer of 1941.

Barton Bernstein, one of the premier historians of the early years of the US nuclear programme, with a low tolerance of dramatic license, has pointed to a number of errors, some more serious than others, none of which appear in the Sherwin-Bird biography, and which I confess to have missed completely when watching:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Comment is Freed to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.