On the edge

My week in the NHS

Back in 2021 I had an operation for Crohn’s disease that went very wrong and got stuck in hospital for a long time. I wrote about it here, as it’s why this substack exists. It also led me to get interested in health policy, and in particular the NHS’s struggle to improve productivity (I co-authored this report for the Institute for Government).

One of my lessons from the experience was not to ignore medical problems in the hope they’d go away. Unfortunately, it turns out I’m not very good at learning lessons.

Over the last few years I’ve been having issues with my kidneys, almost certainly related to that 2021 operation – having a stoma means you dehydrate all the time. Once again I’d ignored all the signs, and avoided seeking medical help. Once again, this did not end well. Eventually it got bad enough I had to go the GP and discovered my kidney function was dangerously low. Which led to a trip to A&E, an emergency admission, a small operation, and a long term problem.

As before the experience offered a lot of insight into the state of the NHS, and got me thinking about the way systems are organised in inefficient or unproductive ways. The doctors and nurses who treated me were uniformly excellent, but, when I got a chance to speak with them, were deeply frustrated at the system they were working within. So here are five things I learnt along the way.

1. Why GPs don’t do blood tests any more

The first problem I encountered was getting a blood test on my kidney function in the first place. I knew I had a serious issue, and my GP agreed. She wanted me to get the test done urgently. But my surgery – like most GPs these days – no longer does them in house. The first appointment I could get online, with the phlebotomy centres contracted by my local integrated care board (ICB), was a week away. Because I’m willing to make a fuss I re-contacted the GP and persuaded them to make an exception so I could get a same day test. But a lot of people wouldn’t have done that, particularly amongst the most vulnerable groups – like those with poor English, or mental health issues.

Why don’t many GPs do blood tests anymore? Because they’re not paid for them. Phlebotomy is not included in their core contract, so unless they’re separately contracted to do them, they get no money. Some ICBs still pay GPs to do it as a separate service but many contract hospital trusts or private providers instead.

In theory this could be more efficient by having fewer centres processing more tests. But in reality it inevitably causes continuity of care problems. There’s no way of knowing how many people don’t get a blood test done because they can no longer have one at the point where its been requested, but it won’t be a small number.

Contracting out at scale can also cause its own problems. Synnovis – a public-private partnership – were commissioned in 2021 to run blood tests for 200 GP surgeries in South-East London, but were hit with a cyberattack last year, leading to significantly reduced capacity and a lot of wasted appointments and false results. Even before the cyberattack they were struggling, according to a BBC report. One trade-off for scale efficiency is creating single points of failure.

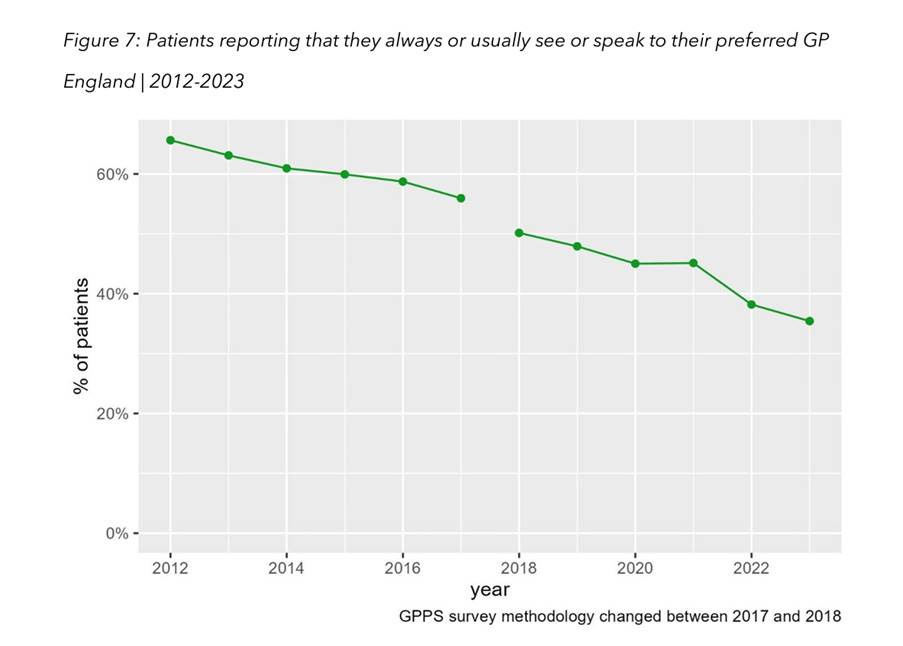

This all goes to a wider point I discussed in a post last year on primary care. Due to a shortage of GPs, and a desire for greater efficiency, tasks that used to be done by GPs or in their surgeries are increasingly being shared across a wider group of professionals and organisations. This adds process to the system – because requests need to be triaged to different people – and also reduces continuity of care. People are increasingly unlikely to see the same doctor repeatedly. Which in turn leads to higher numbers of unnecessary A&E visits and admissions for avoidable conditions like hypertension. Again this is most likely to impact more vulnerable groups.

2. Why A&E is so slow (part one)

When my blood tests came back they showed my kidneys were functioning at around 20% normal level. Not good. My GP told me to go to A&E. I had a copy of the blood test results and I knew, from talking to the GP, that I needed a CT scan. This is what happened but it took six hours to get there even though, when I did eventually get the scan there was no queue in radiology, and hadn’t been all day.

On the way to getting the scan I was seen three times. First, when I arrived, by a nurse making an initial assessment so that I could be sent to the right part of A&E. Then by another nurse and then, eventually, by a junior doctor. She then had to get a more senior doctor to sign off the scan. Thus the delay.

Some kind of process to triage patients run by more junior staff is necessary. It can’t be done by senior doctors as they need to be focused on the most serious cases (which I wasn’t). But at no point did I have a proper triage conversation. The initial assessment was done very quickly – within 90 seconds – so that they could process everyone coming through the door. The second nurse then took a blood test because she’d been told to, even though I already had one. It wasn’t until I saw the doctor, after five hours, because we had to wait for the blood test to come back, that I could explain my situation.

Back in August I attended a different A&E because my stoma was blocked (yes I know, I’m a mess). This was smaller and outside London, but there my initial assessment was with a more experienced nurse with whom I had a proper conversation. She got me in front of a more senior doctor faster who was then able to directly order a CT scan. Maybe it’s impossible to do this in a large London hospital. There is good evidence, though, that using advanced triage approaches where trained nurses are empowered to order various tests and start treatments are more effective (and are used in some NHS hospitals). The faster someone is able to make a decision, the quicker things move.

3. Why A&E is slow (part two)

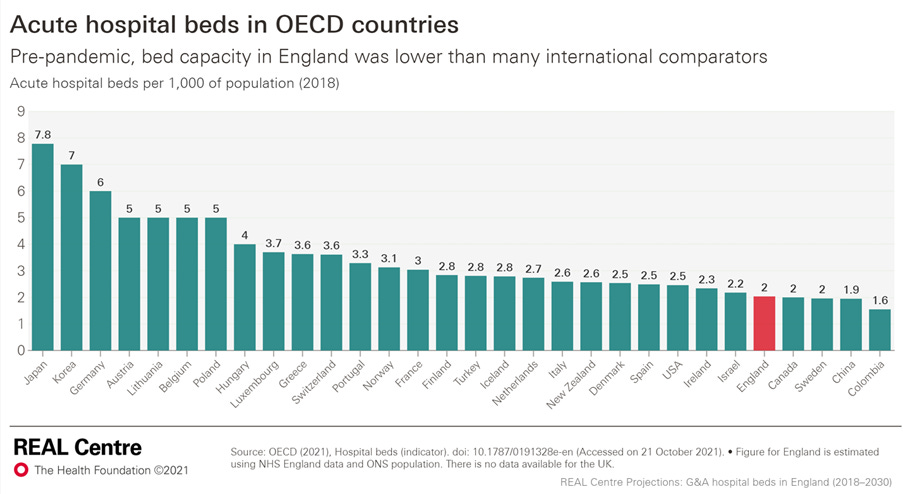

But by far the biggest reason why it takes so long to get seen in A&E – particularly in big urban hospitals – is that there aren’t enough beds to admit people into. I’ve written before about my bemusement at the refusal of NHS hierarchies to accept this basic fact. They have a tendency to see hospital beds like roads, worrying that traffic just expands to fill the available space. All the focus in recent white papers, under successive governments, is on getting people out of hospital and treated in primary/community care or smaller local centres.

The persistent over-optimism about the achievability and benefits of doing this means we’ve lost far too many hospital beds and have fewer per capita than almost any developed country in the world. So there simply isn’t enough space for the demand that exists. This is partly because of the slow speed of discharging patients - both because of problems with social care and poor processes. But even if these were improved (and social care isn’t going to fixed anytime soon) there is also just a basic capacity problem.

Because we have an aging, and sicker, population keeping roughly the same number of beds means that effective capacity will keep falling in coming years. Bed occupancy across the NHS is now higher than it was before the pandemic: reaching 92.5% earlier this year. In the Trust I was in it averaged 98.1% in the last quarter. We are, once again, massively exposed if another crisis hits.

After I had my CT scan – which showed a stuck kidney stone on my right side and both kidneys full of smaller stones – I saw a specialist who decided I needed to be admitted for an emergency procedure the next day. At which point I was sent to the inner sanctum of A&E with all the other people waiting to be admitted but with no beds to admit them to. There were a lot of us all sat on chairs in varying degrees of distress.

This takes up valuable A&E space but more importantly it takes up a lot of staff time. Nurses, and occasionally doctors, were having to treat people in these chairs who should have already been admitted. I was being given regular antibiotics and was set up on an IV drip. But other cases were more complicated. All this staff time couldn’t be spent dealing with new patients. This is the main reason why A&E waiting times have gone up so much, even though staffing has risen more than numbers attending.

It was two in the morning before a bed could be found for me. And I was lucky, plenty of people have been stuck in those chairs all night. I could cope but a fellow patient sent up to the ward at the same as me was an 80 year old diabetic and had been waiting 12 hours since his decision to admit. This is not conducive to good health outcomes. An ONS analysis earlier this year found that “patients who spent more than 12 hours in hospital accident and emergency departments were more than twice as likely to die within 30 days than those who were seen within two hours”. Last month just under 45,000 people waited more than 12 hours from decision to admit to admission, 15% up on the same month the previous year. We need more hospital beds!

4. Why information matters

One of the worst things about any hospital trip is the lack of information about when you’re going to be seen or what it going to happen to you. Admittedly, I’m something of a control freak so find it particularly unbearable, but you’d have to have zen-like calm not to get frustrated.

The A&E was bad enough, but then when I did get on to the ward it got worse. I was told I was on an emergency surgery list for that day but with no sense of when I might be seen or what the likelihood was. Because it’s an emergency list, if someone turns up in a life-threatening condition they get seen first, for obvious reasons. So there’s no way I could have been given an exact time. Fair enough. The issue was I got no information at all about where I was on the list or when things changed unless I (or my long-suffering wife) nagged the poor nurses, who had better things to be doing.

On that first day I didn’t get seen at all, despite not being allowed to eat or drink in case I was able to have the surgery. The next day we went through the same process. Eventually at 5pm I got taken down to surgery and had the procedure (they tried to get the stone but couldn’t so fitted a stent between the right kidney and my bladder).

Again the core problem here is capacity. The hospital doesn’t have enough operating theatres to deal with all the emergencies coming in, plus their elective lists. Indeed, elective patients, many who’d been waiting months, or even years, were being bumped due to a lack of space. This was despite the doctors doing their absolute best to fit everyone in.

Given the NHS’s capacity issues, though, it makes information flows to patients even more important. Patient satisfaction is, unsurprisingly, correlated with wait times. But being given information significantly reduces dissatisfaction. People tend to be willing to wait if they know why. They’re also loss averse. Being given over-optimistic assessments of wait times makes people particularly unhappy.

This matters for two reasons beyond the value of keeping patients happy itself. First, because patient satisfaction affects health outcomes – increasing likelihood of engaging in treatments and following advice. (Though attempts to boost satisfaction by giving patients exactly what they want can lead to overtreatment and wasted tests). Secondly, unhappy patients waste a lot of staff time because they’re trying to find out what’s going on. Being constantly pestered for information reduces productivity.

Imagine if when you got to A&E you could download an app which told you which doctor you’d been assigned to, how many people he or she were seeing ahead of you, and the estimated wait time. When someone had been seen (or was added ahead of you because they were more in need) it would update to show your new position in the queue.

Or for my emergency surgery list, I could have been given a screen showing where I was in the queue, that updated when new, more serious cases, were taken in. Yes, this would require some changes to processes, and it might not seem like the most pressing issue given the capacity challenges. But it would vastly improve the patient experience and thus health outcomes and productivity, at relatively little cost.

5. The NHS is increasingly over-reliant on staff overtime

One issue that came up a lot when researching the IFG productivity report was the importance of staff working unpaid overtime to the functioning of the NHS.

According to the NHS staff survey, the amount of unpaid overtime is roughly static over the past decade – though it increased a lot during the pandemic. Around half of all NHS staff say they regularly do extra hours for no money – with around 10% saying this is more than six hours a week. It’s higher for some groups than others – 27% of consultants say they do more than six hours a week. Older staff are generally more likely to work more unpaid hours (presumably because they’re more experienced so there’s more pressure on their time).

What has changed is that all age groups are doing more paid overtime hours as well. Around 30% of hospital nurses are now doing six or more hours a week on average, compared to 13% back in 2013.

Added together this means a lot of staff are working a significant number of extra hours on top of already long and exhausting shifts. This was evident to me during my stay. The day shift nurses nearly all stayed well beyond handover to complete notes and finish discharging patients. The junior doctors all looked absolutely exhausted, twice I spoke to specialists who were physically out of breath having run across the hospital.

The issue is less due to a lack of staff per se – numbers of doctors and nurses have risen faster than patient numbers since 2013 – and more a function of the wider capacity problems. Staff are having to spend much more time than before working around the lack of beds, theatres, diagnostic equipment and so on. They are also having to spend a lot more time with patients who shouldn’t still be in the hospital. I spent three days as an inpatient for a simple procedure that took half an hour. That’s a lot of unnecessary nurse time doing my observations, giving me drugs, and being pestered by me for information.

The most recent data I can find, from the Health Foundation in 2023, showed length of stay for emergency admissions rising from 7.9 days to 9.1 days between 2019 and 2022, reversing the pre-pandemic trend. Assuming this still holds that’s around 8 million additional bed days a year being used due to longer emergency stays. Which is a lot of extra work.

Given all this it’s not surprising that staff morale in the NHS remains below pre-pandemic levels and that 70% say they sometimes or often feel burnt out because of work. Numbers have improved a bit from the lows of the pandemic, as has staff retention, but the trends remain concerning. Perhaps the most worrying indicators are about early career nurses. The numbers of UK-educated nurses leaving within five years of registering rose by 67% between 2021-2024. And the numbers applying for nursing degrees have collapsed.

On the edge

I write a lot about the NHS but there’s nothing like experiencing itself yourself to highlight how fragile the whole system feels at the moment. Hospitals are making enormous efforts to increase productivity, with some success, but only by running at close to full capacity – with no leeway. This is exhausting for staff, trying for patients, and means that if anything goes wrong there’s no room for manoeuvre. A very bad winter, let alone another pandemic, could easily push everything over the edge.

As for me – I’ll be fine. It was a frustrating week but I got treated and remain grateful to live in a country where I didn’t have to bankrupt myself to do so. The system just about worked. But to quote one doctor who was apologising to me for delays “I’m sorry - it feels like the whole place is falling apart.”

Glad it urned out well in the end. I think your experiences are fairly typical, although I have seen some great efficiencies achieved through the use of community diagnostic centres that keep you away from hospital sites for procedures such as scans. But then the problem comes with poor communication between the bits of the NHS who are then responsible for the next steps. The 'scope of practice' issues that require 'decision escalation' definitely need review.

A further issue I've seen is the NHS estate. At a local hospital the other day only one set of lifts was working. So patients on beds who needed to be moved around needed to be taken on long journeys around the building and waited in queues just to get in the lift. This meant porters were delayed. They told me this was quite common and caused significant backlogs throughout the hospital. Hospital management are reluctant to invest in the building as they have been promised a significant re-build; in the meantime people just have to cope with the challenges of poor infrastructure.

The changes needed are compounded by the scale and complexity of the NHS and often the 'reforms' we introduce add to the muddle instead of streamlining. I'm not sure we spend enough time and energy understanding the patient journey and making the small, logical changes that would make that even a bit better for the next time.

Sam it was your initial article about your experience in hospital that impressed me so much and I have followed you ever since. How you can be so dispassionate while so ill is quite stunning. Keep well and keep us informed, your substack with your father is a must read.