We are delighted to have a guest post today from Sir John Curtice, Senior Research Fellow at the National Centre for Social Research and his colleague, Director of Analysis, Lovisa Moller Vallgarda.

For those of you who don’t follow British politics closely, Sir John is the public face of election data crunching here. He will be the lead analyst for the BBC on election night and also manages the team that produces the exit poll. So this is roughly equivalent to Sir Paul McCartney writing a post for a rock music substack. It’s a fascinating piece, looking at the values driving the behaviour of different voter groups, and raising some big questions about the future of British politics.

We’ve made this post free to read. But throughout the election we’re publishing daily briefings for paying subscribers. You can get them by turning on notifications from your “manage subscriptions” page (found by clicking the menu in the top right hand corner of the web page - it’s easier to do on a browser than the app).

In the last few days we’ve continued the seat-by-seat previews, covering 62 constituencies in central London, Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire, and Cambridgeshire and Essex. We also had a great overview of how things have changed in the polls since the start of the campaign and what that tells us. Next week there’ll be 100s more seat previews plus, tomorrow, an aggregation of all the MRP polls to see where they agree and where they don’t. You can become a paid subscriber here:

And get a gift subscription for friends or family here:

Mapping Voter Coalitions

Sir John Curtice and Lovisa Moller Vallgarda

We are responsible for one of the most ambitious research projects on British voters at this election, one which is not an exercise in trying to predict the outcome of this particular election.

That is not to say we are not as interested as the rest of you in those latest MRP predictions of what the outcome might be in terms of seats. But to understand the patterns of voting behaviour and electoral coalitions that will underlie the outcome of the election, we have taken a deep look at the values that are influencing voters’ choices and which will help structure the patterns of party competition across the country.

Beyond the campaign drama of the rise of Reform and falling levels of support for both Conservative and Labour – and indeed the political turmoil of the last five years – there is a far more stable structure to voters’ preferences lurking beneath the surface.

In this guest post, we list three things you should know about the electorate, introduce a conceptual map of the British opinion landscape, crack open the black box of MRP prediction models, and offer you all a chance to assess how the character of the electorate varies from constituency to constituency.

Three things you should know about the electorate:

1. We are in an era of unstable voter coalitions. Even a very large majority is no longer a safe ticket to a decade long rule – just look at what has happened to the fortunes of the Conservative party in the second half of the 2019-24 Parliament. Labour may now have gained support across the electorate because voters think the party may be more competent than the Conservatives. But the coalition it has built consists of voters with diverse ideological views. Consequently, it could well be fragile and hard work to maintain. That is crucial to understanding the longevity of Labour’s support (or lack thereof), and the tightrope the likely winner will need to walk after 4 July.

2. In contrast, the electorate’s political values are far more stable. There are topics that are prominent in this election that mattered less at the last election – arguments about the state of the health service, the state of the economy and who you think will provide a more competent government. These are undoubtedly things which are important to understanding the flux of our politics in the last five years. But there is a danger in focusing on that, and then coming to the conclusion that other big questions about the future of our country do not matter to voters. Or that the Brexit debate no longer influences what voters are going to do. The underlying values of the voter segments that wanted to ‘get Brexit done’ did not change even though the focus of the political debate has done. Bear in mind that the subjects that are the focus of political debate and voters’ concerns now may not be the same in five years’ time.

3. The opinion landscape parties need to navigate is two-dimensional. Politics in Britain is no longer simply a battle between ‘left’ vs ‘right’. It is also a debate between social liberals who value diversity and social conservatives who prioritise social cohesion. Meanwhile some sections of the British public are much more engaged in politics than others. As a result – and after crunching an awful lot of data – we argue that you should think of the British electorate as consisting of six segments, each with a unique profile and combination of values. Moreover, although voting intentions may well continue to fluctuate rapidly in future, shifts in this underlying landscape can be expected to be far slower.

A political typology of Britain

In US politics, the Pew Research Center has provided a helpful map for understanding the underlying structure of ideological dividing lines within the electorate that the parties are seeking to navigate. For our own analysis of the electorate and how their values relate to party politics in this election, we needed a similar conceptual map for Britain.

At the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen), we have mapped out the underlying views and values of the British electorate by assessing which values and attitudes tend to cluster together, drawing on the enormous amount of data collected by the British Social Attitudes survey.

As a result of this analysis, we invite you to regard the battle for British votes as a balancing act that involves appealing to six distinct types of voters:

Middle Britons (26%) are the largest segment and in many ways the ‘typical’ British voter. On issues of inequality that divide ‘left’ from ‘right’, they believe ordinary people do not get their fair share of the nation’s wealth but are not necessarily up for tax-and-spend policies. On the social liberal/social conservative dimension they believe we need to be tough on crime and are somewhat concerned about immigration levels, but are largely neutral on equal opportunities issues. They are not especially interested in politics.

Well-off Traditionalists (12%) have views that align closely with traditional socially conservative values, including being concerned about immigration and not being particularly favourable towards welfare spending. At the same time they are economically right wing, they dislike the prospect of redistribution, and believe the trade unions are too powerful.

Apolitical Centrists (17%) do not follow the news closely and they are disinclined to back change in either direction. Rather, they sit in the middle on many economic and social issues and, for example, tend to believe that levels of immigration and welfare spending are about right.

Left-Behind Patriots (15%) are left-wing on questions of inequality, reckoning for example that the better off are not taxed enough. However, at the same time they are decidedly conservative in their social outlook. They are critical of equal opportunities policies, believe in stricter sentencing, and are proud of Britain’s history. At the same time, they are disenchanted with politics.

Urban Progressives (16%) are left-wing, socially liberal and very engaged in politics. They want to direct wealth away from big business and from earners and towards ordinary working people. At the same time, they believe immigration is good for Britain and think we have a lot further to go on equal opportunities for all.

Soft-Left Liberals (14%) believe in civil rights, are supportive of immigration, and accept as British those who feel British. But their social liberalism is combined with a more centrist outlook on economic issues. They would, for example, like more public spending but might not back increased taxes on high earners. They also tend to be interested in politics.

These segments are not only very different in their political views but also in their likelihood of voting at all. In our British Social Attitudes interviews, one in four Middle Britons and Left-behind Patriots, and a staggering one in three Apolitical Centrists, told us they likely wouldn’t bother. The other three segments, in contrast, are very likely to vote.

Four of the voter segments – all but the Well-off Traditionalists and Urban Progressives – also have weak (if any) party loyalties. It is those four segments where the parties are more likely to gain – or lose – electoral support.

Are you a Soft-Left Liberal, or perhaps a Well-off Traditionalist? Some of you might identify yourselves straight away on this list. Others might be slightly further from the centre of one of the six clusters. We’re offering you twelve questions; give us those answers and we will identify the group with which you are most closely aligned, based on how 5,578 representative, randomly selected adults across Britain responded to those very same questions.

Stark demographic divides

Anyone who has been on the campaign trail will have clocked that the opinion landscape of the ‘Red Wall’ is not the same as that of Brighton. An effective way to map this is to make use of the link between the values we hold and the distinctive demographic traits of those who belong to the six groups.

Well-off Traditionalists are, for example, likely to be white British, religious and perceive themselves as at the higher end of the social ladder. Urban Progressives and Soft-Left Liberals are typically university educated professionals, but the latter group are somewhat older and thus better paid and more established in their careers.

In contrast, Middle Britons mainly reside in small cities and towns, are less likely to have gone to university, and are more likely to be female. There are more women among Apolitical Centrists as well, but as a whole they are a bit younger than Middle Britons and part of this group struggle on their current income. Half of Left-behind Patriots have no A-level qualifications or their equivalent.

These patterns are not dissimilar to the demographic divides in voting intention, albeit they are more stable over time. In the same way that voting intention is modelled, we can make use of this link between opinions and demography to generate constituency-level estimates.

Predicting views in a specific constituency – a crash-course in MRP

Small Area Estimation (SAE) methods, such as MRP, have grown in prominence in a range of research areas over the last two decades. It is all based on a similar premise – plug the gaps in what you know by ‘borrowing strength’ from supplementary data. The more data you gather, and the stronger the association between what you are trying to predict (e.g. voter types or voting intention) and the data you have gathered (e.g. demographic data), the better you will do.

Multilevel regression with poststratification (MRP) combines survey data with information about the characteristics of Parliamentary constituencies (or other small areas) to produce more accurate estimates of views, values or behaviours in those areas. The work is done in two stages.

First, relationships in the survey data are analysed. The survey data is often linked up with additional data at this stage, to help generate better predictions. We include detailed local area information about the location the respondent lives in, and YouGov’s (who describe their MRP method here) additions include information on the candidates standing for different parties in the constituency. This linked data is used to generate a model that predicts your outcome of interest. In our case, we’re predicting voter type. It’s possible to use multilevel regression for this - that’s the MR in MRP. We use machine learning (ML) instead. More on that later.

Second, the prediction model that was generated in that first step is used to create an estimate for a specific constituency. This second step relies on having a highly detailed dataset that covers all the predictors your model requires. The process is known as poststratification – that’s the P in MRP.

To generate predictions, our project team used a machine learning classification algorithm, whereas more traditional MRP uses multilevel regression. We deemed a machine learning approach more suitable, given that we are estimating as many as six potential voter type allocations and taking into account possible non-linear relationships. For us, this decision was driven by wanting to ensure that the model performed as well as possible on the data we’re working with.

Our model can correctly predict which voter segment a randomly selected British adult belongs to in about one in three cases, based solely on that person’s demographics and local area information. That might not sound all that impressive. However, once you aggregate these assessments up across all adults in a constituency, model accuracy improves dramatically. A person you have mistakenly classified as an Apolitical Centrist might have turned out to be a Middle Briton, but another person in that same neighbourhood is statistically highly likely to have been miscoded in the opposite direction.

In estimating the distribution of our six voter profiles across the 575 constituencies in England and Wales, NatCen took into account 5.3 million combinations of personal and neighbourhood characteristics, using Census 2021 (ONS) data linked with other administrative data. For each of these 5.3 million combinations, we use our model to predict the likelihood of a person with these exact traits in this exact local area belonging to each voter type. We multiplied each of our predictions with the number of adults it applies to. Finally, we added all these individual predictions up to Parliamentary constituency level.

That all became very technical. If you are still reading – let’s get back to the politics.

A constituency look-up of key voter segments and rich demographics

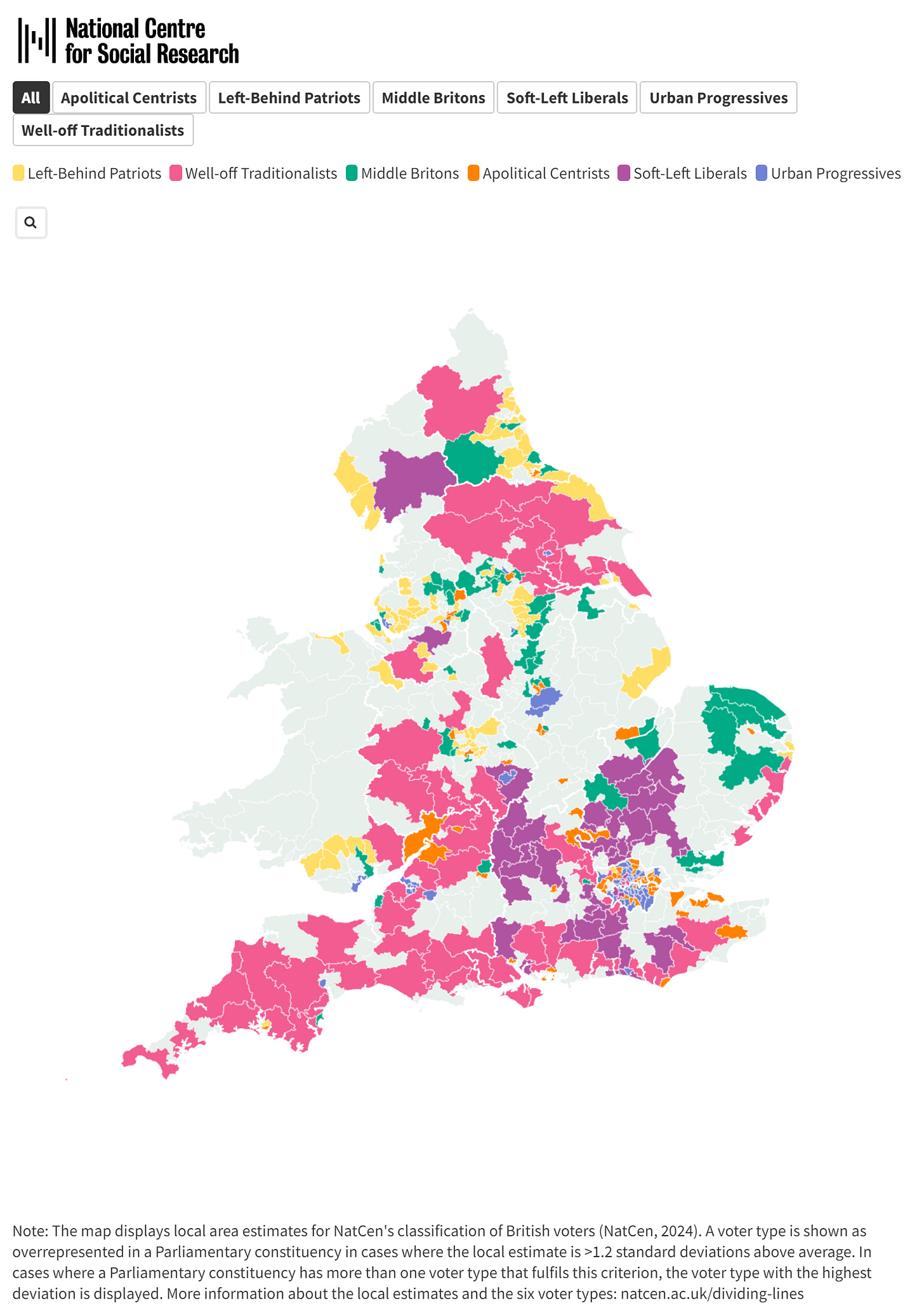

Here’s the map of the English and Welsh opinion landscape our research has generated:

We require a high volume of data to generate quality predictions, and there is unfortunately not yet enough published data from the latest Scottish census for us to generate similar predictions for Scotland. The British Social Attitudes doesn’t yet cover Northern Ireland.

There is an interactive version of this chart available on our site, where you can explore more data on opinion profiles along with highlights from all the demographic data that we gathered by constituency. For example, here is data by constituency on the risk of being a victim of crime:

If you like data as much as we do, we’ve also made a data download available.

Some reflections on target seats and voter coalitions

So how are the six voter types likely to vote? We know from the data on party identification collected in British Social Attitudes interviews that Labour could be on track towards putting together the broadest voter coalition. The party is relatively popular among Urban Progressives, Middle Britons and Soft-Left Liberals. That will not be the easiest coalition to maintain, especially when you bear in mind that there are also some Left-Behind Patriots in the mix.

Based on the same data, the Conservatives could be looking at a coalition mainly consisting of Well-off Traditionalists, Middle Britons and Left-Behind Patriots. Well-off Traditionalists are the most likely of these groups to identify as party supporters. As to be expected, this voter type is likely to strongly dominate many constituencies where the Conservatives had a comfortable majority in the 2019 election, such as New Forest West, and Arundel & South Downs.

Middle Britons are a key target for all the parties. Many do not identify as supporters of any party and those that do are divided between Labour and the Conservatives though other parties pick up some support too. They are also plentiful in key marginal seats. Among the 90 English and Welsh seats where the Conservatives had less than a 20% lead over Labour in 2019, Middle Britons are the largest group in two-thirds, comprising in each case at least a quarter of the electorate.

In contrast, Soft-Left Liberals are especially to be found in many of the so-called ‘Blue Wall’ constituencies where the Liberal Democrats appear to be the main challengers to the Conservatives. This group provides the Liberal Democrats with the nearest thing that they have to a core supporters base.

The 30 English seats where recent YouGov and Ipsos MRPs predict that Reform UK will do especially well are characterised by the high prevalence of two opinion profiles: Middle Britons and Left-Behind Patriots. We estimate that there are relatively high numbers of these two groups in 28 and 23 of these seats respectively. In our party identification data, Left-behind Patriots and Middle Britons together with Well-off Traditionalists were identified as most inclined to support Reform. Put Clacton into our constituency look-up and you can guess what you might find.

In contrast, the seats which the Greens are targeting do not always appear to be ones where their strongest potential supporter base is overrepresented. True, the Greens are focusing on Brighton Pavilion and Bristol Central, both of which have high concentrations of Urban Progressives among whom the party does particularly well, followed by Soft-Left Liberals. In contrast, North Herefordshire is a different kind of constituency. To win there, they would likely need to rely on at least some Middle Britons or (perhaps surprising to some) Left-Behind Patriots.

That’s enough speculation for one guest post. Once John has completed his duties for Britain's TV election coverage, we will assess in which of the six segments each party actually does well and badly in this year’s (post-election) round of British Social Attitudes interviews and analysis. Until then, we hope that you will find the map of the electorate useful. It might even make the political behaviour of the electorate make a bit more sense.

Great. Took the 12-question test and am an uncategorisable weirdo. I mean, not unexpected, but harsh to be told so by Sir John Curtice.

Very interesting post.

It's JOHN CURTICE!!!!

Basically this is like meeting the king, but for psephologically-obsessed weirdoes.