Speaking to headteachers at the moment one topic comes up time and time again: the mental health of their pupils. It feels very much like a crisis but figuring out exactly what is going on is not straightforward.

There’s no doubt that referrals to the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) have gone through the roof. In 2019/20, over half a million children were referred, an increase of 60% since 2017/18. The pandemic caused another surge. By June last year there were 51% more children in contact with CAMHS than before the pandemic.

CAMHS was already struggling, despite a substantial cash injection during the last Parliament, and is now in crisis, with many young people having to wait months, often over a year, to get an appointment. An alarming number of referrals are being rejected, even after attempted suicides or self-harm. Clearly the most recent surge was caused by the dislocations of covid, with young people missing both their friends and the structure of school. There are some hopeful signs that the return to school is calming things down a bit.

However, the trend for higher referrals was well established before Covid and is likely to continue. This prompts two questions: are things really getting worse, or are we simply noticing things now that we didn’t before, as people are encouraged to talk about mental illness? Secondly, if things are getting worse, why?

Is children’s mental health really getting worse?

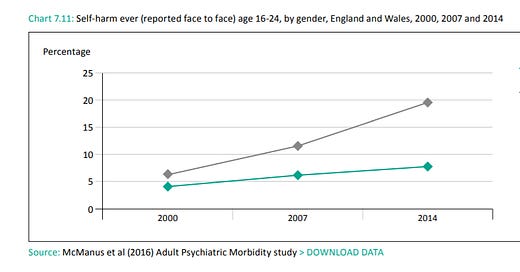

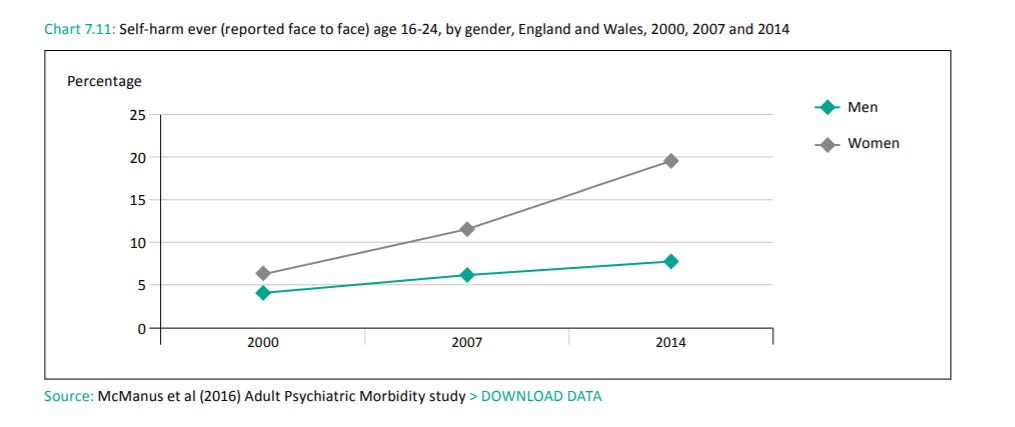

The first question is harder to answer than you might think. Good trend data is surprisingly tricky to track down. Probably the best survey of the available data is the chapter on mental health in the Association of Young People’s Health Key Data publication. Data on reported self-harm is perhaps the most alarming. 20% of young women aged 16-24 told a face-to-face interviewer in 2014 they had self-harmed, three times higher than in 2000. But this could be partly a result of reduced stigma.

Hospital admissions for self-harm between 2011/12 and 2017/18 also shows substantial increases for 10-19 year olds, and you’d expect that to be less affected by changes in attitudes.

There is also a peer reviewed analysis of primary care datasets which shows a substantial increase in self-harm cases, particularly amongst teenage girls, as well as in eating disorders and a massive jump in anxiety disorders for the same group. In each case there was a big jump around 2012.

The rise in cases, referrals and even self-harm leading to hospitalisation doesn’t definitively prove these trends are because mental health is getting worse. It remains possible it’s related to de-stigmatisation but given the range of evidence and the fact that the biggest increases relate to a specific group (teenage girls) and a specific set of issues clustered around anxiety and body image I would assign a high probability to it being a real issue. Especially as it fits the anecdotal conservations I have with headteachers and parents.

Is social media the cause?

If we accept this problem is real – as the data seems to be suggesting it is – then the next question is why is this happening? If it’s hard to prove the trend is real, it’s even harder to prove any cause. One of the most commonly identified culprits is social media. Until recently I’ve been sceptical for two reasons. First I’m allergic to moral panics. Every new technology from the novel onwards has been accused of poisoning young minds. Remember when “video nasties” were going to end civilisation? Or more recently violent video games? (Despite a lack of evidence either causes more real life violent behaviour).

Secondly as Stuart Ritchie points out in this excellent article, to date the evidence assembled by proponents of the social media theory like Jonathan Haidt and Jean Twenge, has shown correlations not causal relationships. Yes, it seems that young people who use social media a lot have worse mental health, but that could easily be because young people with worse mental health choose to use social media more!

But recently I’ve shifted to thinking it probably is a major cause for three reasons:

1. I can’t think of anything else that fits. Other suggested causes just don’t work. Some people argue it has something to do with schools and a harder curriculum / testing regime in England. But this doesn’t fit the evidence. Firstly because this problem is happening all over the developed world and England is pretty much the only country to shift towards a more “traditional” curriculum / exam system. Secondly there’s no evidence - this clever paper by Professor John Jerrim shows no difference in wellbeing across UK nations for eleven year olds, despite English youngsters being the only ones to sit a formal test at that age. Finally, the big surge in cases seems to have started before changes to exams/curriculum.

It can’t be poverty either because, although children in poverty do have worse mental health outcomes, numbers weren’t increasing during the Labour or Coalition Governments (though they have more recently).

Social media does fit, the big increase in take up maps well on to the mental health data and it happened everywhere in rich countries at the same time. The most affected group, teenage girls, are also the ones who report that social media makes them more anxious and body conscious in focus groups (see e.g. this EPI report). It is of course true that correlation doesn’t prove anything but if there’s only one strongly related correlation it’s pretty likely there’s a relationship.

2. There is no doubt that young people are spending a huge amount of time online now. And that, therefore, must have replaced other activities that involve being out with friends in real life. Three quarters of 12 year olds now have a social media profile and 95% of teenagers use social media regularly. Over half who say they’ve been bullied, say it was on social media.

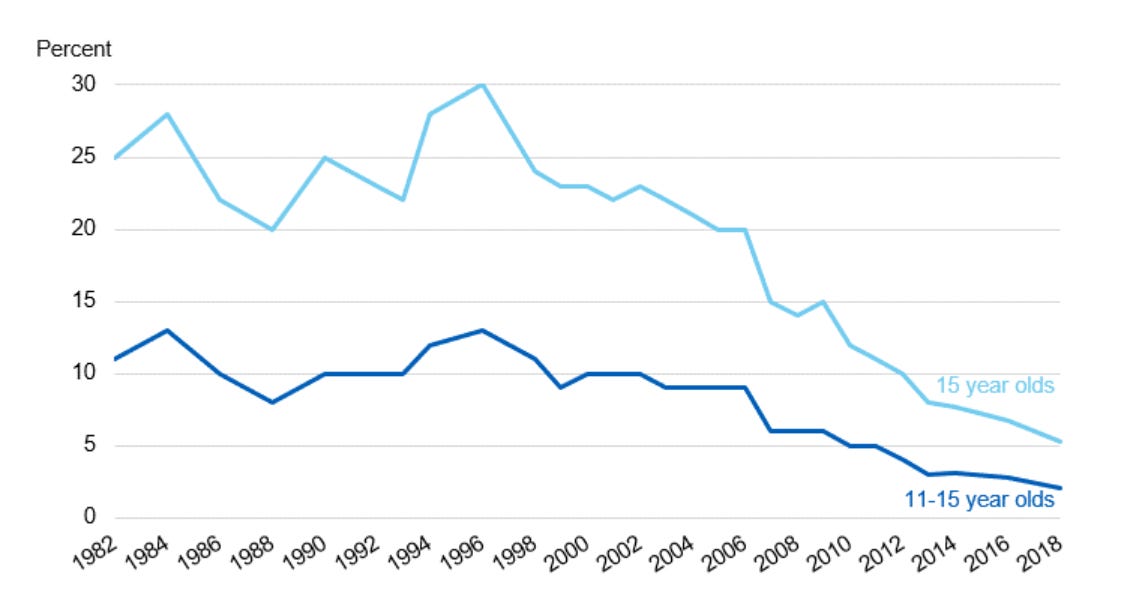

One corollary of this is that “real world” negative behaviours have dropped massively. This chart showing the number of children smoking regularly is one of the most encouraging in public policy.

You might argue numerous health initiatives and increased prices are behind that fall (though the big drops map on to increasing computer and then smartphone use). But we can see the same patterns with alcohol and illegal drug use (albeit not for cannabis use). The same is true for involvement in crime.

It seems likely that the impulses which led previously to real world bad behaviour are going to find other outlets in a more online world, but are going to be a) more hidden to adult authority and b) lead to more internalised forms of harm. After all adults drink and smoke to reduce their anxiety.

3. We finally have the first evidence of a direct causal relationship via a very clever US study using the staged rollout of Facebook across US college campuses to assess the impact on mental health. Not only does it show that mental illness increased after the introduction of Facebook but it also shows that it was particularly pronounced amongst those who were more likely to view themselves unfavourably alongside their peers due to being e.g. overweight or having lower socio-economic status. It is just one study but it nudges me even further towards thinking this a major cause of the problem.

But even if we assume that this is right, it’s still not clear to me what the right policy response is. Children ignore existing age regulations (most sites in theory don’t allow under 13s to have accounts, but they do); so it’s unclear what further regulations would achieve. Pressure could be put on Facebook and others to improve the design of their sites and support mental health initiatives. But, again, it’s unclear what the legal route would be if they chose not to. In China the state is intervening directly to restrict youths’ computer time, but that’s not an option in a democracy.

Others with a better grounding in what is possible technologically may have better suggestions. In the meantime I have blocked my (12 year old) twins from all social media apps and will hold out as long as possible. The evidence isn’t yet rock solid but it’s solid enough to make me want to protect them as best I can.

One of the big problems is that if social media is causing harm its far from clear what it is about social media that causes harm. Social media is a variety of features assembled in different ways in a series of different products. There are lots of potential candidates for which part could be harmful but they all have different implications for what you need to do about it. A short list could be: increased exposure to photos of themselves, an increased exposure to idealised photos of others, a pervasive online messaging environment making it harder to escape bullying at home, increased exposure to content about self harm or mental illness, more explicit social competition through likes/shares/comments or increased exposure to other content that is stressful. As Stuart Ritchie pointed out in his article not only is the external evidence not that strong but platform's own internal evidence to date hasn't been that great either. That makes it very difficult to put pressure on Facebook to improve the design of their site as its not very clear what they need to improve.

It also makes it very difficult to give good advice to parents about what apps children should avoid. The features that could cause harm exist in varying extents in a wide variety of apps from, YouTube, to Instagram to WhatsApp to even some apps targeted at children like Roblox. The trend is to include more of these features in a greater variety of apps so its harder and harder to say that one set of apps is social media and another set is not.

On what the state can do it about, the UK Government's approach is probably best seen through the Age Appropriate Design code which sets out what platforms should think about for designing services that could be used by under 18s rather than thing targeted at under 18s: https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/guide-to-data-protection/ico-codes-of-practice/age-appropriate-design-a-code-of-practice-for-online-services/ Broadly its part of a wider movement that platforms need to be designed and regulated for the presence of young people unless they can absolutely guaranteed that they won't be used by them. I'm not sure that's the right approach but it is one worth talking about.

First evidence link is broken for me