The Tory party is in a big hole at the moment. The UK is in a recession which the Bank of England thinks will last into 2024; the Government is about to announce a bunch of unpopular tax rises and spending cuts; Boris Johnson has left them without any kind of coherent agenda; and they are 20pts behind in the polls. Rishi Sunak’s position is unenviable.

Electorally one of his biggest challenges is holding on to the new voters the Conservatives picked up in 2017 and 2019 following the EU referendum. They are disproportionately older home owners who are instinctively authoritarian but also well to the left economically of your average Tory MP. One reason these voters felt able to move across last time (often via UKIP) was that Boris Johnson significantly softened the austerity rhetoric, more money was promised for schools, hospitals, the police and ill-defined “levelling up”. They have already started drifting back to saying they’ll vote Labour in considerable numbers, following partygate and then the Truss debacle, and the imminent announcement of austerity round two isn’t going to help.

It's not surprising then, that many Tories see immigration as a key topic to keep these voters on board. A group of Theresa May’s former advisers including her chief of staff Nick Timothy, and her pollster James Johnson, have been particularly vociferous on this point. Another member of this group, Will Tanner, who Timothy hired into No. 10 back in 2016, has been re-hired by Sunak as his deputy chief of staff.

Sunak seems receptive to their arguments. He didn’t intend the scandal around the immigration processing centre at Manston to be leading the news in his first few weeks but leant into it – supporting aggressive statements by Suella Braverman, including calling asylum seekers crossing the channel in small boats an “invasion”. Despite his reputation as being more moderate and sensible Sunak has never publicly wavered in his support for draconian asylum policy, including the Rwanda deportation proposals, on which a judicial decision is expected any time now.

The politics of migration

From a short-term electoral perspective you can see the logic – that group of 2017/2019 switchers are typically strongly anti-immigration, even if the population as a whole has become more liberal on the topic. In 2016 54% of voters told the British Electoral Survey they wanted to see fewer immigrants and 14% wanted more. Those figures are now 42%-29%. But the immigration sceptics remain the larger group. It’s also a potentially tricky area for Labour as their base trend strongly liberal but they also want to win back that same group of switchers. The sorts of internal rows that can lead to were illustrated by the reaction to Keir Starmer’s comments at the weekend that the NHS has too many overseas workers.

But there are two big problems with this tactic.

First, while aggressive rhetoric will appeal to many Tory voters it is also off-putting to demographic groups they need if they are to save seats in more liberal areas of the country. They are defending 20 seats in London, at least a dozen more in the South-East, and six in Scotland, where they need the support of more liberal voters. Given they only have a majority of 70 now they can’t afford to lose all of these. Nationally the public were evenly divided on whether the “invasion” language was appropriate but in London it was 61%-28% opposed and in Scotland 54%-32%. Polling by the charity More in Common has found divergent views between the group of voters they call “Established Liberals” – the sorts of professionals David Cameron attracted to the Tory party and “Loyal Nationals” who are those UKIP switcher types. 55% of the latter group think immigration is “much too high” but just 23% of the former.

Despite this Tory strategists may decide it’s worth the risk. There are more seats where a stronger stance against immigration would help than hinder, and perhaps it’s simply impossible to hold their 2019 coalition together anymore. It wouldn’t be an unreasonable calculation to sacrifice some seats like Esher and Chipping Barnet in return for having a better chance of holding a swathe of provincial towns. The far bigger problem is that those more authoritarian voters think they’re doing a terrible job on immigration.

We have, after all, had twelve years of tough talk on the subject from Theresa May, Priti Patel, and now Braverman. Every manifesto has promised lower annual numbers yet they are higher than ever. Brexit dealt with the vexed issue of free movement but it didn’t change our economic model which is now heavily reliant on overseas labour. A government prepared to fully commit to a different model could have tried to do so by whacking up investment in adult skills and retraining in 2016 – at least in sectors like medicine where there is demand amongst Brits to do the jobs for which we are currently dependent on migration. Instead skills funding is 25% lower than it was in 2010, medical school places have been cut, and now it’s too late to change anything in time for the next election.

In the short term there is literally no practical way the government can materially reduce immigration without causing immense damage to key sectors of the economy and public services. They can’t even go after foreign students, whose numbers have increased as a deliberate public policy decision in recent years, because university finances are now almost entirely dependent on them given years of frozen tuition fee income for home students.

There is, of course, a difference between economic migration and asylum seeking, albeit one the government continually tries to elide, and which is hazy in the minds of many voters. The public are more supportive of economic migration - particularly for certain sectors. For instance 78% of people think we should allow more or the same number of migrants to work in the NHS – with just 7% saying fewer. Perhaps the government could keep quietly allowing more economic migrants in – with the tacit acquiescence of right-wing media who would be foaming at the mouth if it was happening under Labour – but crack down hard on asylum claims? (Notwithstanding that the public are supportive of what they see as genuine claims – 63% say we should allow more or the same number as we do now who are fleeing war or persecution compared to 23% who say less or none).

But in practice they are not. Indeed the numbers of claims are increasing – there were over 63,000 in the year to June, 77% up on 2019 and the highest in almost two decades, the record being 84,000 in 2002 (fig 1). These numbers need to put into perspective – they are much lower than the half a million international students who were granted visas last year or the 330k coming here to work (both numbers that have more than doubled since Brexit). It also a lower number than seek asylum in other large Western European countries, and far lower than Germany or France.

Fig 1: Asylum applications lodged in the UK, years ending June 2002 to June 2022

The issue here, though, is exacerbated by the increasingly long time it takes to process asylum seekers. There are now well over 100k cases awaiting an initial decision – a number that has quadrupled since 2018. Because no one awaiting a decision is allowed to work this means significant financial support is required as well as housing, increasingly in hotels. It’s this that has led to the immediate crisis at Manston as Suella Braverman refused to sign off yet more hotel beds (almost certainly illegally). And it’s this that is creating so much unhappiness amongst Tory MPs, particularly in constituencies with beds in cheaper accommodation that are being bought up by the Home Office. It has been made worse by the slow pace of the Afghan resettlement scheme – half of the 21k who moved here after the fall of Kabul are still in hotels. And the increasing pressure on temporary accommodation from Ukrainian refugees who have not been able to secure permanent homes.

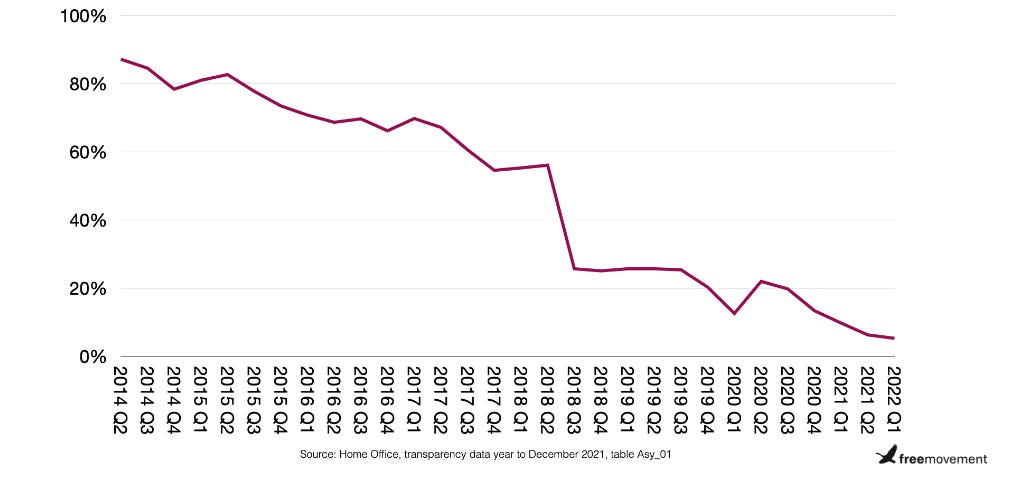

Fig 2: Percentage of asylum cases decided within six months

The failure of the government to grip these challenges is why raising the salience of the issue is so risky for the Conservatives. YouGov find that just 12% of people who voted Tory in 2019 think the Government is handling the issue well and 78% badly. All pollsters have Labour leading on the issue at the moment. After last week, where the issue dominated the news, Opinium found Labour’s lead rose from 3pts to 8pts. Braverman is also very unpopular, by a substantial majority people don’t think she should have been reappointed. The More in Common polling found that 24% of the 2019 Tory voters who would no longer vote for them, said the failure to stop small boats was a main reason for their shift.

Getting a grip

So it seems very unlikely that the Tories will be able to make any political capital on the issue unless they show progress on reducing numbers (though if they were successful at doing so it would make it harder to increase the salience of the issue). This makes Braverman’s re-appointment even more problematic because, regardless of whether you agree with her opinions, she is not a competent minister. Home Office officials are aghast at her basic inability to do the job – as the Manston decision, and the briefing around it, shows. Sunak has tried to mitigate this issue by putting in an ally, Robert Jenrick, as the junior minister responsible for immigration, and he has been doing a lot of the Parliamentary and media heavy lifting. But so far he’s having to spend all his time cleaning up after an incompetent Secretary of State.

The urgency in government to find some alternative solutions to channel crossings is an implicit acceptance that their much hyped Rwanda deportation scheme is not going to provide the answer. Even if the courts allow it – and if they do there will be an appeal to the European courts – it will not act as an effective deterrent. First because even if it’s allowed in principle each individual case will be fought by lawyers; secondly because it’s inordinately expensive so can only be applied to a small percentage of cases; and thirdly because if you’re desperate enough to hand over your life savings to risk a dangerous channel crossing you’ll likely accept the small risk of deportation too. Personally I think the policy is barbaric but a plurality of people support the idea (though it is incompatible with the majority view that genuine asylum seekers be allowed to settle here, which suggests it’s not properly understood). However, a substantial majority also think it won’t act as a deterrent.

If that isn’t going to work then what will? The one thing that is working, to some degree, at the moment is our £60m a year deal with the French that pays them to patrol the channel and turn boats back. As of September 2021 the French were intercepting 57% of crossings but that number has dropped back this year as attempted crossings have increased. The government is briefing that a new deal is in the final stages of negotiation, and that this will increase our payments in return for more enforcement activity by the French, and potentially UK border force officials being allowed to work in France. But the problem is fairly obvious. The channel is only 20 miles across at its narrowest point and it cannot be made completely secure, nor is it hard for people to try multiple times if they are turned back. On top of that immigration is a big issue across the channel too – with Marine Le Pen’s National Rally (formerly National Front) now holding 89 seats in Parliament, so there is not much incentive for Macron to up the numbers of asylum seekers France are taking.

So an enhanced deal with the French makes sense but isn’t by itself going to reduce numbers significantly, or even stop them growing. Indeed it is simply impossible now to stop boats crossing in some numbers – the route is just too established now and it is very hard to get to the UK any other way, given successful crackdowns on asylum seekers trying to get here in lorries or trains. The only way to make it defunct would be to allow people to claim asylum from other countries, but there is no way either this government or a Labour one is going to do that given it would increase applications. Harvey Redgrave, a former Labour home affairs adviser, has suggested doing this with a quota on the numbers allowed each year. But I struggle to see how a quota could be compatible with taking people in genuine need.

Given the difficulty of reducing crossings themselves if I found myself in the unfortunate position of being Home Secretary I’d be focusing heavily on the processing system which is in an absolute mess. Asylum seekers are waiting years to get their claims processed – just 4% of those who crossed the channel in 2021 have been dealt with to date. This is terrible for them, as those who don’t disappear from the system and move into illegal work end up destitute and reliant on the state, and puts huge strain on the increasingly expensive accommodation system. Reports from the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration (ICIBI) show a processing system that exemplifies all of the worst failings in UK policy delivery. The technology doesn’t work: case workers are entering data manually into Excel spreadsheets that crash all the time and don’t talk to each other. Attempts to speed things up through crude targets for case workers have led to morale dropping, huge turnover (40% last year) and inexperienced new starters struggling to make decisions. As a whistle-blower recently told the Observer:

“They’re getting in far too many inexperienced people, with no understanding of the asylum system, and they just don’t have the support they need so they leave….It’s a total disaster. They don’t know what they’re doing”.

It’s hard to know how much of a “pull factor” our broken processing system is for asylum seekers, and particularly the criminals who facilitate crossings and also run drug dealing gangs in the UK, but it seems reasonable to think it is a factor, given that it’s relative easy to disappear from our system. As the recently published inspection report into the initial processing of small boat asylum seekers put it:

“Data, the lifeblood of decision-making, is inexcusably awful. Equipment to carry out security checks is often first-generation and unreliable. Biometrics, such as taking fingerprints and photographs, are not always recorded. The Home Office told our inspectors that 227 migrants had absconded from secure hotels between September 2021 and January 2022, and not all had been biometrically enrolled. Over a five-week period alone, 57 migrants had absconded – two-thirds of whom had not had their fingerprints and photographs taken. Put simply, if we don’t have a record of people coming into the country, then we do not know who is threatened or who is threatening.”

So the first step I’d take as Home Secretary would be to direct as much resource as possible into processing – not just speed but also building stronger long-term systems. Assuming this is a priority for the Prime Minister I’d insist on additional funding plus regular stock-takes with the PM to ensure the civil service, at all levels, gave it top priority. Significantly reducing processing time would help asylum seekers with a genuine claim to settle here and start working faster; would reduce any pull factor associated with the ease of disappearing; and would save the taxpayer significant amounts in accommodation and subsistence costs. It would, effectively, end the sense of crisis even if similar numbers of arrivals continued.

The failed claims puzzle

My other focus would be looking at returning asylum seekers whose claims are not accepted. At the moment a historically high number of claims are being accepted – 76% at the last check. It’s not entirely clear why the number has gone up so much and because the processing is so slow it’s also not clear it would apply to the asylum seekers crossing the channel this year. For instance we won’t know for a while what proportion of the large number of Albanian men arriving this year will have their claims rejected if they stay in the system.

But even with so many claims accepted there are still many thousand that aren’t and the Home Office has got much worse at getting them to leave the country. In 2010 there were over 6,000 enforced removals of asylum seekers whose claim had been rejected. In 2021 it was 113 (fig 3). Again it’s not clear why this has dropped so much, it seems to be a combination of lack of prioritisation and resourcing from the Home Office plus those who lose claims getting better at avoiding enforced return.

Fig 3: Returns of former asylum seekers

One point of dispute is whether Brexit has made any difference here. When we were in the EU we were part of the Dublin Agreement which allows signatories to return asylum seekers to the country they arrived from (rather than their initial country of origin). Brexiteers are dismissive of Dublin because we didn’t use it very effectively and indeed ended up taking more asylum seekers from other countries, mainly children looking to be reunited with parents, than we sent back. But it may nevertheless have acted as a deterrent and it certainly could have been used more effectively. The Home Office team responsible was profoundly dysfunctional even by their standards, with a serious bullying problem, hopeless retention, and a lack of resources.

I would want to explore re-joining Dublin – there is no need to be an EU member to do so. It was considered in Brexit negotiations but the UK proposals weren’t taken seriously because they were so one-sided. On top of this I would, as with processing, be looking to focus resource and attention on this area – it was something that David Blunkett and Tony Blair did manage to improve through relentless pressure on the system. There have been calls to introduce ID cards as a way to make this easier though it’s unclear how it would help as asylum seekers already have them and employers/landlords have to do ID checks already.

Improving Home Office capacity to manage returns, as with processing, would take time, money and a change of approach from Government. They have wasted large sums fruitlessly attempting to find some magic, press friendly, solution to the problem that doesn’t exist. Had they devoted the resources ploughed into the Rwanda scheme to processing we would have much less of a problem now. Had Priti Patel not forced officials into exploring endless madcap schemes such as attempting to stop dinghies being sold in channel ports (smugglers just started buying them online) they could have put the effort into identifying why returns had fallen so much. If the Tories want to make immigration a big part of their next election campaign they need to get serious fast, and that should start with a new Home Secretary.

Many thanks to barrister and immigration expert Colin Yeo for helpful thoughts and info - his site https://freemovement.org.uk/about/ is the best resource for understanding the complex issues around the topic. All opinions and errors are, as ever, mine alone.

Also many thanks to Luke Tryl of More in Common for sharing the polling tables cited in this Times article. Where there isn’t a link to polling mentioned in this piece it’s from those tables. If/when they are put on line I will add links.

On the electoral side of things, it feels like Tory strategists think it's still summer 2021, when the question of whether it was better to tilt towards Guildford or Grimsby was a relevant question. But of course on their current trajectory they are going to lose both seats, and indeed every seat that they had been mentally trading off against each other.

This is an outstanding overview and analysis of a diabolically complex situation. Thank you.