As we inch our way closer to the general election, coverage is going to get ever more feverish. The long reads will get more breathless; minor policy announcements will be picked over as if the future of the nation rested on them; in hundreds of polls of varying type and methodology, each minor deviation will be jumped on as proof of a dramatic shift in public opinion; combinations of cliches bundled together in tedious speeches will be subjected to endless speculation about they what really mean.

This could easily become unbearable. So here are five tips on how best to wade through all this coverage. What are the signals you should be looking for in all the noise? And what can you happily ignore?

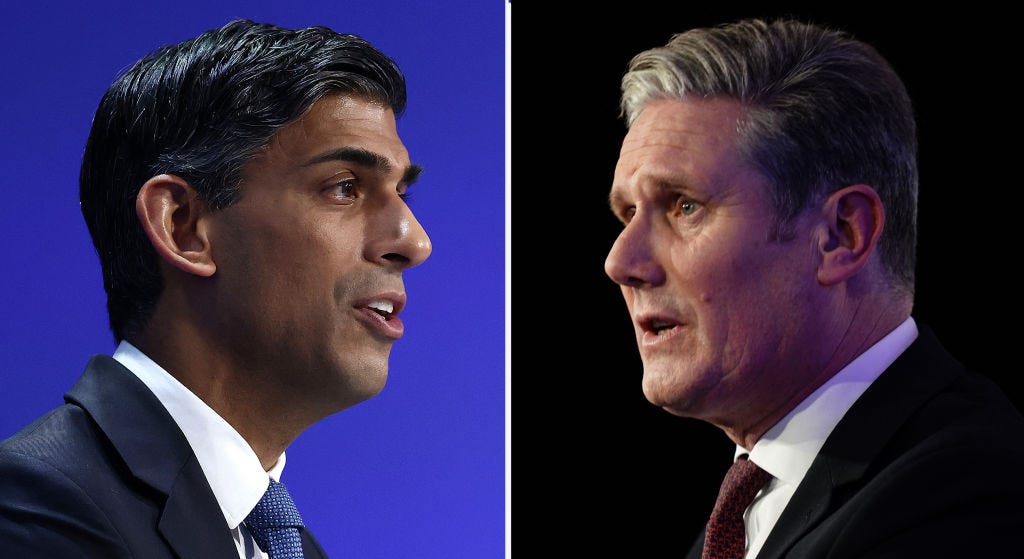

But before that a quick note on timing: the election is going to be in the autumn, it was always going to be in the autumn. Thankfully Sunak has dampened the speculation somewhat by saying that. He hasn’t killed it as there is nothing stopping him changing his mind. But, barring a miraculous change in the Tory poll ratings, it will be in the autumn. When exactly in the autumn is not important, but it will probably be later rather than earlier given the strategy is to wait for people to notice economic improvements.[i]

1. Don’t overread polls

I’ll start with a tip that should be obvious and yet remains widely ignored. There are now ten polling companies doing regular surveys in the UK plus another three or four who do them sporadically. That’s about 40 polls a month and as we get closer to the election many of those firms will start polling more regularly. In the past YouGov have moved to daily polls during the formal campaign. With all these polls these is a lot of random variation due to the margin of error, for most that’s 2 or 3% in either direction.[ii] In December the pollster “We Think” had Labour leads of 16pts, 20pts, 21pts, 14pts, and 17pts. That is just natural variation – nothing changed in the real world to account for those differences.

On top of that we will get, just by the law of averages, occasional “rogue” polls that are wrong outside the margin of error.[iii] These can get people very excited, especially if they happen close to polling day. Ten days before the 1997 election an ICM poll found the Labour lead at just 5%, everyone went mental, but it was rogue.

All of which means the best thing to do for now is just check polling averages. Politico do one as does Sky. That will keep you from freaking out over movements in single polls. Averages aren’t perfect because pollsters use different methodologies, leading to persistent “house effects”, which can’t all be right. But for now they show direction of travel far better than trying to scan every poll. As we get closer to the election I will delve into the different methodologies, why they produce different numbers, and which ones I think make most sense.

2. Poll leads are only part of the story

Most coverage of polling, even if avoids too much emphasis on random variation in individual polls, focuses exclusively on the gap between the two main parties. This does, of course, matter. But in a first past the post system the ways votes are distributed matters too. A lot. In 2005 Labour won by three points and had a majority of 66. In 2010 the Conservatives won by seven points and were 20 seats short of a majority. That was all about distribution.

Which means projecting a result from poll numbers is not at all straightforward.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Comment is Freed to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.