Earlier this month I wrote about how boomers represent the ultimate failure of Margaret Thatcher:

“The very group of people she enriched, by giving them property, increasing the value of it, helping them become shareholders, allowing them to keep more of their income, have not become vigorously self-reliant, leading to a resurgence in entrepreneurial spirit, dynamism, and charity. They have become spectacularly entitled. (I shall pause briefly here to note I am talking about averages here and there are no doubt many lovely and self-aware boomers reading this, not least my business partner/father).”

Most of those commenting and emailing agreed with the sentiment, including boomers who felt included in my caveat, but it also led to some pushback. Even if I was merely talking about the majority of boomers rather than everyone, “spectacularly entitled” is a punchy phrase, and seemed unfair to some. Chris Giles wrote a piece in the FT a few days after my post came out headlined “OK boomer, you’re more generous than we thought” in which he argued that:

“Some older Brits might well be insensitive to the difficulties many younger people have with the high cost of housing and other expenses, earning themselves an “OK boomer” put-down. But as a generation, they are not frittering away their wealth on fast cars and cruises….”

Rather they are saving it to hand down to their children as inheritance. Giles also notes the significant amount of unpaid childcare and social care done by older people. He goes on to argue against my suggestion of higher wealth taxes on the grounds they are unpopular and ignore these benefits.

Stephen Bush followed up on Chris’s column with a couple of additional points. First that voters are well aware that much of the wealth will be passed down through the generations which helps explain why wealth taxes are, in his view, so unpopular:

“There is no shortage of wonks and politicians arguing there are unfair disparities between the old and young. But while there are plenty of willing sellers of narratives about ‘intergenerational warfare’ at Westminster, this has few buyers in the country at large because most voters understand that they benefit from the wealth and inheritance of their older relatives.”

And that, in any case, the real issue isn’t intergenerational unfairness but the old story of class inequality:

“It’s a misread to see UK wealth inequality as a product of generational unfairness. It’s just the same old story of wealth inequality. It looks like generational unfairness because advances in medicine in general and cardiovascular treatment in particular make it look that way, but that’s not the real story…the real political divide that matters is between the “will haves” (people who will either inherit wealth or benefit from family wealth in the present day) and the “won’t haves” (who do not have a family inheritance to look forward to or to draw down on).”

Chris and Stephen are two of the reasons I’m an avid FT reader, so when they disagree with me it’s definitely going to make me check my thinking. The disagreement isn’t total, I agree the pensioners of Britain are not frittering their cash on Ferraris and bottles of Cristal. When I talk about boomer entitlement I mean opposition to giving any of their gains to the state, not demanding a luxury lifestyle. I also discussed the growing importance of inheritance on wider wealth inequality in my post. But I do disagree on two things. Firstly I think generational unfairness is a real thing in itself, related to, but independent from, general wealth inequality. Secondly, and partly because of this, I think we have to introduce wealth taxes, particularly on residential property, if we are going to move towards a fairer society.

That’s why, in the conclusion to my post, I framed these taxes as a break from consensus on a par with the Attlee government’s nationalisations, or Thatcher’s willingness to squeeze jobs as the price of bringing down inflation. If you’d told someone in 1978 that the next government would increase unemployment to over 3 million within two years and then go on to be in power for 18 they would have sent you to a psychiatrist. Breaks in the consensus do happen, it just requires every other option to be exhausted first.

Intergenerational unfairness is real

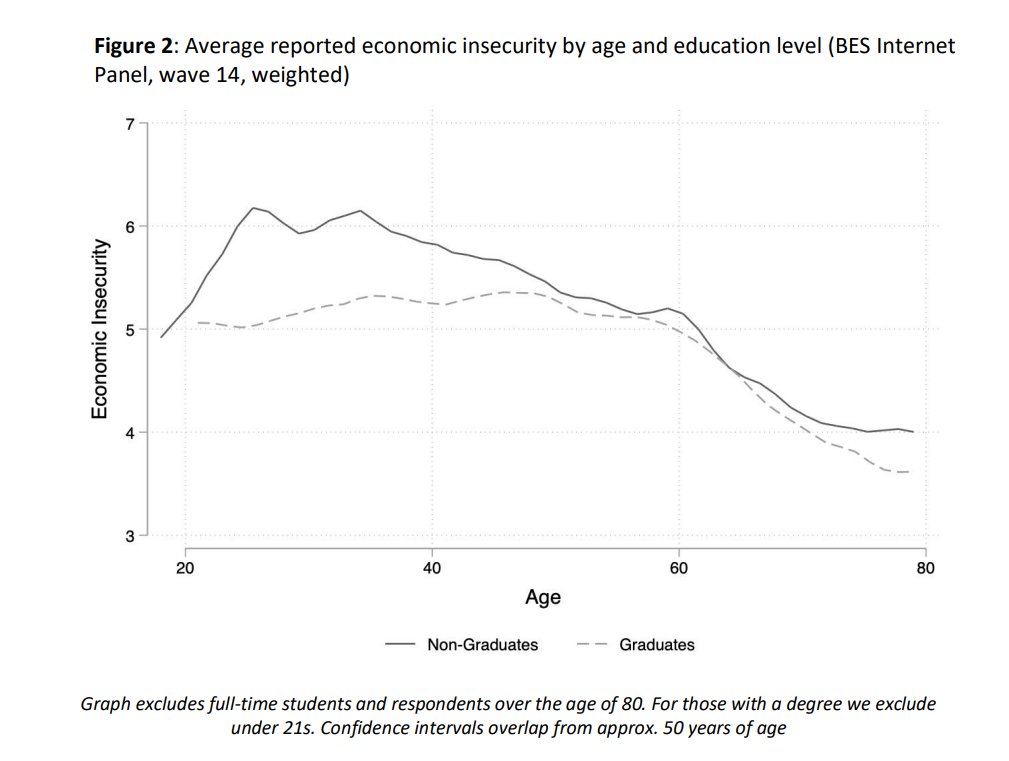

No one could seriously deny – and neither Chris or Stephen are do – that older people are better off than younger ones at the moment. As the chart below from Professor Jane Green and Roosmarijn de Geus, based on British Election Survey Data, makes clear there is a strong relationship between age and economic security.

Moreover this relationship has strengthened significantly in recent years for two reasons. The first, and biggest, is, you guessed it, house prices. Older people bought their properties before a huge surge in value made them far less affordable. With much lower housing costs (and without other costs like childcare, tuition fees, and transport) they are economically secure on a considerably lower income than younger people. 75% of pensioners own their homes outright, up from 55% in 1993. Meanwhile people aged 35 to 44 years are almost three and a half times more likely to be renting than they were in 1993.

At the same time state subsidies to older people have increased relative to those for the working population due to triple lock state pensions, generous private pension tax reliefs, and the rising cost of the NHS and social care. Back in the mid-90s there wasn’t much difference between the proportion of pensioners in poverty and the number of children – both were around 30%. But now it’s 15% for the former group and still 30% for kids. The problem here is not with the subsidies for older people – it’s emphatically a good thing that pensioner poverty has dropped, and I certainly don’t want to see NHS funding cut – but that there has been no equivalent generosity for younger generations. Larger families in particular have been hammered by benefits cuts – the Resolution Foundation project that almost 80% of those with four or more children will be in poverty within the next few years. At almost all income levels the costs of childcare, housing, taxes, and tuition fees, have made starting a family much harder for millennials.

Stephen is right to say that:

“State spending is always going to be U-shaped. People like me, in the middle of their lives, without children or complex health needs, will always rightly be subsidising people at the beginning or the end of their lives. The actually important debate is over the degree of subsidy, not the fact the subsidy exists.”

But it seems to me hard to argue that the levels of subsidy haven’t become unbalanced over the last fifteen years in particular, and that has led to intergenerational inequality.

It is undoubtedly true that much of the wealth being accumulated due to this lack of balance will ultimately be passed on to boomers’ children. However, this will not end generational unfairness without other policy changes. For a start the age at which the inheritance is received is increasing. As the IFS note:

“The average age of people when their last-surviving parent dies is expected to rise from 58 for those born in the 1960s to 62 for those born in the 1970s and 64 for those born in the 1980s. For about a third of people born in the 1980s, this will not happen until they are in at least their 70s.”

In other words the bulk of bequests will be received near the point of retirement, and will likely trigger early retirement for many. It will still leave younger generations, at the age to start families, without support. Now of course people don’t wait until they die to pass money down and many Generation X-ers and Millennials will already be receiving financial help from their parents.

But this is an incredibly inefficient way to do wealth transfer. Understandably older people will be risk-averse and want to ensure their own lives are secure, in case they require extensive social care in the future, thus limiting what they are prepared to pass down. Moreover the vast bulk of the wealth is trapped in housing and is not being accessed. Equity release is becoming marginally more popular but it is still rare. 13,000 people released £1.7 billion in the third quarter of 2022, which, when you consider UK housing is worth over £8 trillion, is a drop in the ocean. All of this means that only 20% of under-35s have received a substantial gift from their parents, more than in other countries, but still leaving four-fifths without help in affording a property deposit, wedding, or child.

It is, of course, also the case, as I discussed in my initial post, that inheritance is distributed in a wildly unequal way. According to the IFS:

“One fifth of people born in the 1980s have parents with wealth ‘per heir’ (i.e. after dividing it equally between their children) of less than £10,000, but 25% have per-heir parental wealth of £300,000 or more and 10% have £530,000 or more.”

So even if we accepted that intergenerational unfairness was the wrong lens it would still be the case that we’d need to consider wealth taxes to deal with general wealth inequality. But as I hope I’ve shown in this section there is also a widening generational fairness gap and that will not close naturally. Both because state subidies will continue to disproportionately target older people and because most bequests will be made when boomers’ children are themselves at or close to retirement. This gap is the result of policy choices and it needs to be tackled with policy too.

The case for wealth taxes

I think both Chris and Stephen overstate the unpopularity of wealth taxes versus ones based on income. Chris cited a recent post by Ben Ansell which explored the data in detail but is more nuanced. Inheritance tax and stamp duty are certainly extremely unpopular. But capital gains tax and council tax are only considered marginally less “fair” than income taxes. And the idea of a wealth tax on the assets of the richest households is popular, though, as Ben rightly notes, no one thinks *they* are the wealthiest. Moreover, Ben showed that how you frame wealth taxes changes how they are perceived so there is openness to persuasion:

“Emphasising double taxation pushes people to become about ten percentage points more likely to think inheritances taxes are too high compared to the baseline group. By contrast, emphasising the benefits of lower income taxes and higher public spending led to a decline of just under ten percent points in people thinking inheritance taxes were too high.”

We also have an extensive analysis of public attitudes to a wealth tax by MORI in 2020, commissioned by the Wealth Tax Commission. This found people significantly preferred the idea of either a new wealth tax or increasing council tax/capital gains tax to higher income tax or VAT if more government revenue was needed. Again taxes targeted at the wealthiest were particularly popular. But even if we accepted that wealth taxes were unpopular that would not be a good reason to avoid the issue unless there is a better solution elsewhere. Chris argues that:

“We should stop looking at the rise in private wealth as a magical source of revenue to solve society’s problems and instead focus on what else we can do to attack the lack of social mobility — the main downside of wealth cascading down the generations. This would mean, for example, governments redoubling efforts to increase the supply of housing to limit rental costs for those without access to the bank of Mum and Dad. Universities must continue successful programmes to increase access for more disadvantaged students. And it provides a justification for workplace diversity schemes that increase opportunities for people from different backgrounds.”

This is highly unconvincing. We should do all these things but the idea that by themselves they could make much of a dent against the huge power of wealth accumulation is fanciful. You can run as many diversity schemes as you like but if children are growing up in grinding poverty they are unlikely to get anywhere near university or a graduate internship. And increasing house supply will only have a marginal impact on prices. In reality tackling social inequality requires greatly increased expenditure on welfare benefits for families, subsidised childcare, the reintroduction of maintenance grants for students, more investment in non-academic routes for post-16 year olds, and greater investment in housing. All of this requires money and that money has to come from somewhere. Higher taxes on income would only put more pressure on younger workers, so that means we have to look at wealth.

If we accept the idea of wealth taxes the next question is what should they look like. One option would be reforming our existing taxes that relate, at least in part, to assets rather than income – capital gains; inheritance; and council tax. At the moment none of these taxes – by design – are good at getting at the primary source of wealth increases: residential housing. Capital gains excludes main residences; inheritance tax offers generous allowances for a family home so most will avoid paying tax on it; council tax has little relationship to the actual value of a property. As Sam Bowman puts it:

“Council tax [is] specifically designed not to increase in line with rising house prices – it’s pegged to what a house was worth in 1991, or what a newly built house would have been worth if it had been built in 1991. The total amount raised from council tax is about £42bn, on £8.4 trillion of residential property wealth…..So housing in the UK receives extremely favourable tax treatment compared to other investments, and increases in the value of houses have been almost entirely shielded from tax. The aggregate value of UK housing has risen by +75% (£3.6 trillion) over the past decade, little of which will be caught by capital gains tax.”

These taxes could be reformed to capture more of this wealth but it’s not straightforward. Inheritance tax really is very unpopular, partly because it’s paid as a lump sum and partly because it’s associated with the death of loved ones. Capital gains on main property would disincentivise selling (and would also be wildly unpopular). We could do a council tax revaluation but that’s not the only issue with it. Even if we had correct valuations it would be a regressive tax because the bands are wide and amounts don’t rise much as you go up through the bands. Average net council tax is only 2.7 times higher for the top 10% of properties than the bottom 10%, whereas average income tax is 45 times higher in the top income decile than the bottom one. The typical council tax bill in 2015/16 was 10% higher in London than the North East, while property values were 220% higher.

Rather than try and reform council tax and/or use the highly unpopular inheritance tax, we could try an idea that has been around for a very long time and has always been popular with many economists – a land value tax. This is, in it’s simplest form, a proportional tax on the value of land that you own – say 0.5% of the value paid annually. This would be much more progressive than council tax and, depending on what level it was set at, raise more money. In a recent column Martin Wolf – yet another reason to be an avid FT reader – made the case for a land value tax:

“Now that western politicians are struggling with low growth, stressed public finances, high inequality, intergenerational tensions and an unstable financial system, they need to consider such a fundamental change in what is taxed…. The land under my house has, for example, increased enormously in value over the past few decades. I did nothing to earn this. It was the result of the efforts of all those who contributed to making London richer, including, of course, the public at large, through their taxes.”

He acknowledges the political challenges of this but argues it can be done, and we need to try as we’re running out of other options:

“Evidently, there would be sizeable transitional problems, not least the changes in the valuations on which mortgages have been agreed. One way around this could be to introduce the new taxes on land only on values above those of today. Another would be to phase in the new taxes slowly. Crucially, if there exist reforms able to make the country as a whole better off it is in principle possible to compensate the losers we care about and still make everybody else better off. There are few such policies. Be bold. Try this one.”

The Resolution Foundation set out proposals for a similar tax in 2018. Exactly how we tax wealth, and specifically housing, is, though, a second order question. The key point is that without taxing property wealth more effectively it’s hard to see how we can afford the social changes required to get the country back on track, or bring house prices under control. Voters may not be immediately favourable towards the solution but younger ones are certainly feeling the consequences of the status quo. I would argue the fact that millennials are not moving towards the Tories as they get older is evidence that they do “buy” the intergenerational inequality argument, even if they wouldn’t always express it in those terms. If Labour in government also do little to help this group the frustration will only grow. I don’t see how either party can do what is needed without breaking the taboo on wealth taxes.

‘...this has few buyers in the country at large because most voters understand that they benefit from the wealth and inheritance of their older relatives.’

Of course, the young wouldn’t need to benefit from all these wealth transfers if housing policy hadn’t been ruined by their parents’ generation... Something they didn’t have to deal with when they were buying their first properties on much smaller deposits and earnings ratios. And we then wouldn’t need to answer the wealth taxation question.

FWIW I did a large piece of analysis on how a Land Value Tax would work while I was a data scientist at DWP back in 2016-17. It was very obviously a massive win for at least 70-80%+ of households assuming we raised £200-300bn from LVT and cut the same from PIT and NI. I assumed we would abolish NI and the higher and additional income tax rates and raise the nil rate band to about £16k. All of the objections to LVT (such as excess admin) are just completely idiotic, especially once you look at the data. And it has a huge number of positive spillover effects such as encouraging more bank lending to business by supressing land speculation. I shopped it around the dept and got told it was a good, interesting piece of analysis but it was very obvious it would never go anywhere while the Tories are there